Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

WNYC Studios is supported by Zuckerman Spader. Through nearly five decades of taking on high-stakes legal matters, Zuckerman Spader is recognized nationally as a premier litigation and investigations firm. Their lawyers routinely represent individuals, organizations, and law firms in business disputes, government, and internal investigations and at trial. When the lawyer you choose matters most. Online at Zuckerman.com.

Radiolab is supported by Progressive. Most of you aren't just listening right now, you're driving, exercising, cleaning.

What if you could also be saving money by switching to Progressive? Drivers who save by switching save nearly $750 on average, and auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts. Multitask right now. Quote today at Progressive.com, Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. National average 12-month savings of $744 by new customers surveyed who saved with Progressive between June 2022 and May 2023.

Potential savings will vary. Discounts not available in all states and situations.

Squeezing everything you want to do into one vacation can make even the most experienced travelers question their abilities. But when you travel with Amex Platinum and get room upgrades when available at fine hotels and resorts booked through Amex Travel, plus Resi Priority Notify for those hard-to-get tables, and Amex Card members can even access on-site experiences at select events, you realize that you've already done everything you planned to do. That's the powerful backing of American Express.

Terms apply. Learn how to get more out of your experiences at AmericanExpress.com slash with Amex. Listener supported. WNYC Studios. Wait, you're listening? Okay. Alright. Okay. Alright. You're listening to Radiolab. Radiolab. From WNYC. See? Yep.

All right, we're going to begin today's episode at a golf course wedding venue, sort of, with our contributing editor and resident ER doctor, Avir Mitra. Parsi time. Now, one thing you need to know at the jump of this story is that Avir was raised in part in this religion that is mostly practiced in South Asia called Zoroastrianism. In particular, Indian Zoroastrians are called Parsis.

It's not a big religion, less than 200,000 followers. But a fair number of them happen to be here in South Jersey.

They rent out this space once a month to socialize, read scripture, eat tons of homemade Indian food. But this time, Avir, we did not send him there for that. Although it sounds like he did do some of that. This time, he was there to talk with his priest about the mystery of what happens after you die, but not at all in the way that you think.

I'm Lulu. And I'm Latif. This is Radiolab. And we should mention that this episode does deal with death, and there are a few brief graphic descriptions, as well as a couple swear words. Please listen with care. All right, here's Avir. Every time I tell people about how we, I guess, are burial— well, it's not even—I don't know what the word is, not burial. Disposal of the dead. Yeah, I get a lot of weird looks. Why? I mean—

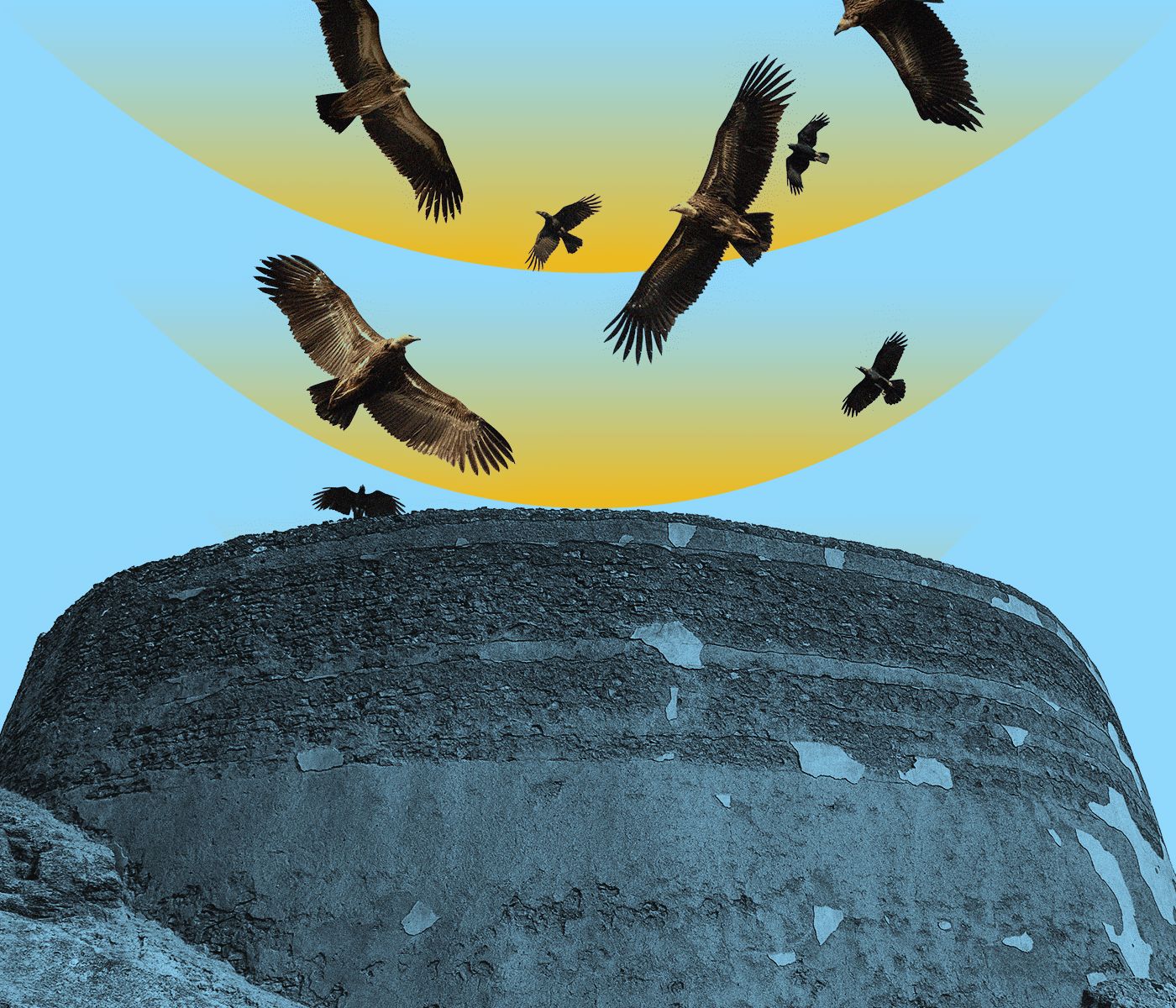

Maybe you could tell me, what is our method of disposal of bodies? The method of disposal is exposure. Exposure? What does that mean? We take our dead to this place called the Tower of Silence. The Tower of Silence? I've been to one in Mumbai. It's this hill in the middle of this big bustling city. But when you get there, it's like just this super forested, quiet area. It almost feels like a jungle. It's so dense.

And at the top of it, there's a flat, like, cement slab in a circle that's open to the sky. Okay. And there's walls around it, but there's no roof on it. And there's different layers to it. The adult men go on the outer edge of this cement slab. Women will go in the middle, and children, if they die, will go near the center. Hmm.

And there's thousands of vultures surrounding this place, just waiting. The vultures would ring the whole walls all the way around, hundreds of them. And then after the body was left, the vultures would descend in that. And yeah, the vultures just devour the body. And within a few hours, all that's left is just a few bones. Whoa. Yeah, we call it a sky burial.

And I don't know, I just think it's incredible. Like in the religion, the idea is that the second someone dies, there's a corpse demon called Nasu. And they believe that that demon is what starts to cause the decay of the body. And so, you know, when the vultures eat the body, they're essentially protecting us from this demon. Oh. Hmm.

So that's one thing. There's also a more practical reason. If you were to bury the body, that's sort of polluting the earth, which they don't want to do. If they burn the body, that's polluting the sky. And they felt that if the vultures eat the body, it recycles it back into nature. So these people were like environmentalists. Yes. They were the original environmentalists. That's amazing. It's pretty metal. It's beautiful. I agree.

And that's the way it is. That's the way it's been for thousands and thousands of years up until 2006. This one Parsi woman named Dunbaria, her mom died. And she had this suspicion. Is my mom in the clear? Has her body been consumed? So she sneaks up into the tower, climbs up to the top. And what she saw there was completely horrendous.

She felt like she had to tell the world. This is CNN-IBN.

There's just bodies. Bloated, rotting bodies, disfigured bodies. Just kind of plopped around that area.

And where you'd normally just see hundreds of vultures at the Tower of Silence, you don't see a single one. The bodies were left to decompose in the Tower of Silence because there were not enough vultures to clean the body, pick the body clean. The vultures are just gone. At the tower? Like everywhere. Millions of vultures.

All over town, all over the state, all over India. Almost overnight, they're all gone. Wow. Okay, so the question is, where the heck did they all go? Yeah, that's the mystery. Which brings us...

when species are in dire straits. - To this guy. - We wear our cape, we swing through the jungles and the forests, and we save the day, right? - A man by the name of Munir Varani. - Here we go. - He's a Kenyan biologist who studies birds. And back in the late '90s, he worked for the Peregrine Fund, which is this organization that basically saves birds of prey. And he had just gotten married, so he's at his new home in Nairobi just a couple weeks into his marriage.

The telephone rang. It was Rick, his boss at the Peregrine Fund. And he said, well, I'm calling you because I wanted to find out, how do you feel about going to India? So he tells his wife, this whole marriage thing's been great. I'm really excited about all this stuff.

I gotta go. So off I went. He flies from Kenya to India, gets off the plane at Mumbai, and one of the first things he does is he starts walking around this park. It's like a tiger reserve. And I remember distinctly this big banyan tree, which is a ficus tree. It's a tree of religious significance in Hindu culture. It's like a tree of life type thing. And what he sees are like... At least 17 vultures that were lying there.

You mean they were dead? They were all dead. They were dead. 17 dead vultures underneath of it. What a stark, like, image. What a metaphor. Just the tree of life and then all this death. Yeah. And this makes no sense to Muneer because vultures are supposed to be super tough animals. Hmm.

Tough like how? I mean, they literally eat dead things, you know? The great thing about living things is they're pretty healthy, you know? They're healthy enough to be alive. Yeah. And so I want to get some of that, you know? Whatever you got going on, I want to put in my belly. But if you died, something went wrong with you.

And now I'm just going to make you part of me essentially by eating you. That's a bold move. But secondly, the second you die, you know, all these bacteria, viruses and fungi that you've been keeping at bay by being alive and having an immune system, you know,

Now, all of a sudden, they start taking over. So the way the vultures survive this is they have a super acidic stomach. It's up to 100 times more acidic than our stomachs. It's like battery acid stomach. Yeah, exactly. Like they can eat anything and it just melts away. Some species also piss and shit acid. Yeah.

Okay. Onto themselves. Poop boots. Yeah, poop boots. Because that keeps the bugs away. It's a little chemical defense. Exactly. Wow. And if someone tries to eat the vulture, some species have evolved this response to just vomit acid on the predator. Wow. That is nearly. Yeah.

And it turns out that all of this is so important because if you think about it, they're basically gobbling up all the diseases and bacteria, rabies, anthrax, all these things. And it stops with them. Like they're the end of the line. They're like nature's immune systems.

Yeah, that's the superpower. And they play such an important role that a bird just keeps evolving to become a vulture. Whoa. This happened four times independently on Earth that we know of, like just across the world. Like, you know what I mean? It's almost like if I came out with like

Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd or something. Like I wrote that album. And then someone else also wrote that album. And like four people across the country just wrote that same album. Why is that your metaphor? I love that. That's a really weird metaphor. And so going back to Muneer looking at this banyan tree, it's super weird that there's all these dead vultures underneath it.

And it gets even more puzzling because these vultures are not like old, decrepit, you know, vultures. And it doesn't look like someone shot them. You know, they didn't like get electrocuted in a power line or something. The birds were in great body condition. They had a lot of body fat. There's just no reason for these birds to be dead. This was like solving a murder mystery.

So Munir's on the case. And what he needs is to get some dead vultures over to a lab in the U.S. Okay. So he goes to India and he's a young whippersnapper and he's like, this is what we need to do. We need to get permits to send tissue samples so that people around the world can look at them. India's like, no, you can't take these tissue samples.

Why are they worried about that? Yeah. You know, it just kind of got tied up in red tape because, you know, India doesn't want people taking their natural products and animals and seeds and wildlife and, you know, making money off of it. Okay. And by the time he's trying to negotiate with the Indian government,

the vultures have already started dying off at a incredibly rapid rate. Like, in India, 95% of vultures are already dead. Oh my god. That is serious. I mean, that is like a just... That's insane. It is. And so he's like, shit, like, what do I do now? So he goes to Nepal, tries again, same thing. They say no. And so...

He decides he's going to go to Pakistan, a neighboring country, and see if he can get some dead vultures there. But... I look in the skies and there are thousands of vultures. And I mean thousands. Wow. You come across a dead buffalo or a cow and there may be 200 vultures that are trying to get into it. But isn't it bad because the vultures don't seem to be dying over there? So you may miss the problem. There's a twist.

We're still finding a few dead vultures. Oh. And they're showing the exact clinical signs. They should not be dead. Right? He's there right before it happens. It's almost like he gets to rewind time just a little bit. So he's like, oh, this is perfect. Like, okay, this is where we should work. Right? But of course, the question lies, are we going to get tissue samples out of that country?

He goes to the main guy in Pakistan, the bureaucrat who's going to give him permission. And he's like, all right, God changed my approach. So how am I going to do this? First of all, the India-Pakistan cricket series was going on, right? And as people know, there's a big rivalry between India and Pakistan. He looks at me and he says, Munir, you want me to give you a permit to export tissue samples? Give me one reason why I should give you that. And I said, Dr. Khalid, no.

If you don't give us this permit, then the Indians will beat you to it. He bluffs. He bluffs. Boom. I just knew I had him. Oh. So they gave us permits to export tissue samples. Wow. Go near. Yeah. So off we started. They get together a group of young research assistants and basically had them pick up these dead vultures and cut them open. And what they see is striking. The inner organs were covered with a white chalky paste.

Does that look like toothpaste? Like, what does it look like? There's like powder, white powder all over the liver, the heart, the lungs, everywhere. Can you wipe it off? Like, it's literally a substance. Yeah, exactly. Weird. So he goes to his senior colleague, this guy, Lindsay Oakes. Oakes takes one look and he's like, oh, I know what that is.

It's kidney failure. Huh? What? It turns out that if you shut down a vulture's kidneys, all this stuff backs up, turns into a paste.

And gets deposited in all the organs. What stuff? What that stuff is, is uric acid. Oh, bird shit. Which is bird pee, bird shit. It's the stuff that's making their pee and poop so acidic. They can't pee it out. And so now it's just depositing in their joints, in their organs. Oh my God. And you die. Wow. So now they know like what's killing the vultures is kidney failure. But no one knows what's causing the kidney failure.

As this story is progressing, the situation's escalating and people are starting to get spooked. So it is happening in Pakistan, too. Yes, it's happening really quick. Like when he first got there, there were 3000 nesting vultures. And the next year it was half that. And the year after that, it was half that again. And four years in, they're down to just 400 nesting vultures. Just like that.

So the leading theory at this time is that this is a virus, right? Because look, it started in Southeast Asia. So they're thinking, okay, maybe going east to west, this virus is spreading. Southeast Asia, Nepal, India. And if this virus moves further west into Pakistan, Afghanistan, into the Middle East, and comes into Africa, where vultures play such an important role, the consequences would be completely dire.

Remember, these vultures are like nature's immune system. They perform probably the most important role than any other animal or groups of animals combined. Like if we don't have them digesting all this bacteria, diseases and viruses, who knows what's going to happen to the entire world. So we're really fighting against time.

Radiolab is supported by BetterHelp. We all like to try to set our non-negotiables, whether it's hitting the laundromat every Wednesday or hitting the gym X times a week. These goals can start to slip when schedules get packed and the mind gets cloudy with stress. But when you're starting to feel overwhelmed, a non-negotiable like therapy is more important than ever. Therapy can help you keep your cup full by giving you the tools you need to get back into balance.

If you're thinking of starting therapy, give BetterHelp a try. It's entirely online, designed to be convenient, flexible, and suited to your schedule. Just fill out a brief questionnaire about all your quirks to get matched with a licensed therapist and switch therapists anytime for no additional charge. Never skip therapy day with BetterHelp. Visit betterhelp.com slash Radiolab today to get 10% off your first month. That's betterhelp, H-E-L-P dot com slash Radiolab. ♪

WNYC Studios is supported by Rocket Money. Did you know nearly 75% of people have subscriptions they've forgotten about? Rocket Money is a personal finance app that finds and cancels your unwanted subscriptions, monitors your spending, and helps lower your bills so that you can grow your savings. Rocket Money will even try to negotiate your bills for you by up to 20%. All you have to do is submit a picture of your bill, and Rocket Money takes care of the rest.

Being a chef means keeping your cool in the kitchen. Here we go.

And with Resi Priority Notify and Global Dining Access through my Amex Platinum Card. Right this way. It's nice to try someone else's food for a change. That's the powerful backing of American Express. Terms apply. Learn more at americanexpress.com slash with Amex.

I'm Maria Konnikova. And I'm Nate Silver. And our new podcast, Risky Business, is a show about making better decisions. We're both journalists whom we light as poker players, and that's the lens we're going to use to approach this entire show. We're going to be discussing everything from high-stakes poker to personal questions. Like whether I should call a plumber or fix my shower myself. And of course, we'll be talking about the election, too. Listen to Risky Business wherever you get your podcasts.

Lulu. Latif. Radiolab. All right, where are we at? Things are looking very grim. Yeah. Yeah.

It seems like all the vultures are dying and it is up to Munir and his team to try to stop it? Yeah, exactly. And, you know, just to step back, we know they're dying of kidney failure. Now, what's causing the kidney failure? In theory, it could be any number of things. It could be a virus. It could be bacteria, fungi. It could be environmental changes. It could be toxins. And so people are testing for this and that, and they're just not finding anything. Hmm.

And then in 2001, Mounir and his colleague, Lindsay Oaks. We were in a meeting in Spain. They're at some sort of bird conference. VultureCon. VultureCon, exactly. They're in their head-to-toe vulture costumes. I can picture it. I can picture it. And you know, this is not a great year for VultureCon. No.

Everyone's covered in talcum powder. And I remember Lindsay and I sitting in the square in Sevilla, sipping espressos. So Lindsay's like, let's just start from scratch here. You know, let's get a piece of paper. They pull out like a napkin and just start writing on the napkin. We were like kids just putting down these flow diagrams, right? Okay. What do we know? Kidney failure. What can cause kidney failure? Toxins. Nothing. Viruses. Nothing. Nothing.

And then Munir says, Lindsay asks this question. He said, okay. That kind of cracks the whole thing open. What's going into the vultures? So it's like, well...

Generally cattle, right? Livestock. And so Lindsay's like, we've been focusing so much on what goes into the vultures. Have we seen what's going into the livestock? So they take a new approach. They go back to Pakistan and they start going around to different villages and just knocking on people's doors, being like, hi, I have a bunch of questions for you about your cattle, you know? And as they're processing the surveys, they're noticing like,

Oh, this phrase keeps popping up over and over again. It just stood out. We give them... Daclofenac.

Diclofenac. Yeah, this drug diclofenac, it's actually a painkiller. It's in this class of drugs called NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. That includes, you know, drugs like Advil, Motrin, Aleve, Ibuprofen. And these farmers were giving diclofenac to cattle because cattle, just like people, you know, get old, get aches and pains. They wake up one morning and they're

Knees hurt. If your cow had a limp and was unable to carry the produce to market, you just pumped it with diclofenac. You just did. And even after the cow gets like too old to pull your cart or whatever, the farmers, a lot of times, at least the Hindu ones, would still give them diclofenac because they're seen as sacred animals. Half of me is Zoroastrian. The other half of me is Hindu. So Hindus, you know, they don't eat cows. I mean, I do eat beef, but don't tell my grandma or whatever. Um,

I'll never forget, I was like in eighth grade and I was like telling my grandma who doesn't speak much English and I don't speak much Bengali. She's like, we don't eat cow. And I was like, yeah, I do because I love burgers. That's made of cow. And she's like, no, no, it's not. You don't eat cow. So then I called my dad into the room. I was like, dad, aren't burgers made out of cows? And he just straight up was like, no, and just walked out of the room. And I was like confused for like five years after that as a child. Yeah.

So anyway, Munir and the team realized that farmers are giving their cattle this drug, this painkiller, diclofenac. So they take some organs, send them to the U.S., and test for levels of the drug. And sure enough, all the vultures that were covered in that chalky white paste came back positive. Huh. Huh. And so suddenly a pattern was evolving. But that's still not a...

I feel like we've gotten, you've connected the dots, but it's the dot that needs to be connected. It's now, it's in the vulture, but we don't know for sure it's causing the sickness. I love that you said that, Latif, because we see diclofenac in the vultures that are dead, but is that the reason that they're dead? And so now we have to show that experimentally. So this is where things have to get really dark. Oh, this story has been just a funfetti cake until now. Yeah, so-

I told you, you know, vultures dying left and right. Munir and his team studying these vultures. They see all these poor baby vultures. These were birds that fell off the nests after their parents died. And so they have been over time sort of sheltering some of these baby vultures and raising them. And giving them what? To feed like little dead rats? Yeah, little dead rats, all little, you know, whatever. Like dead chickens. Bougie vulture. Okay.

These vultures are doing great. And they realize the only way that they can really... Don't tell me. Yeah. Keep telling me. Say it. I don't know where you're going. Where are you going? The only way they can really prove for sure if diclofenac kills vultures is to poison their babies. Okay. They swapped out their perfect Whole Foods meals...

with some buffalo that had been given diclofenac. And they died. And on top of that, they realized all the vultures died in India first because the drug was approved there like four years before it was approved in Pakistan. Oh. So it wasn't an ecological spread. It was a market spread that they were seeing wash across the continent. That's wild. Yeah. It was amazing. It just...

It felt like a huge burden had been lifted off my back. And so in May 2003, Munir and his team go back to VultureCon and Lindsay Oakes gets up on stage and announces it. With his very soft voice and he just talks about the meticulous way... Here's what we studied. Here's what we found. Here's what we did to our pet vultures. Here's what happened. And then there was pin drop silence. And then...

There was this applause that just went on and didn't stop, and people stood up. They all realized, like, this is it. Wait. I guess I'm just wondering, was there any parallel where U.S. vultures dying off? Yeah, I think the difference is, like, we don't care as much about cows in the U.S. Oh, so they're not living... Oh, so they're not... We're eating the meat, so the vultures aren't getting it. Right. We just eat them when they're, like, young and healthy before they have any problems. It's so weird that this is about, like...

caring for the cow makes you want to make the cow not be in pain, which then surprisingly apparently kills all the vultures. Yeah, it's weird. And as a doctor, I can kind of relate to that. I prescribe these NSAID drugs like ibuprofen, Motrin, Aleve, Advil. I prescribe these all the time. And believe it or not, one of the most common causes of kidney injury in humans is

is also NSAIDs. - Really? - Yeah, which is funny, right? Because we were looking at these vultures saying like, oh, that's so bizarre that this diclofenac is messing up their kidneys. Meanwhile, in a different parallel universe of medicine, we're not talking to each other. I don't talk to vulture biologists.

They don't talk to me. Right? Like, we're figuring the same thing out in humans. Wow. Wait, so when was it, like, yeah, when did humans become aware of this? Yeah, it does. There were case studies coming out all along the way. Yeah. But the landmark study was in the year 1999. Okay. Okay.

So interesting, right? Because the vulture thing is happening at the same time. Yeah, yeah. And we've also learned that they can cause intestinal bleeding, strokes, heart attacks. All these problems trickle down from the use of NSAIDs. Whoa, why? Yeah, basically, you know, NSAIDs are inhibiting this molecule that cause pain. And so you take them and you don't feel pain, which is great.

But it turns out that these same molecules do a lot of really important stuff in the body. And so when you inhibit them, you know, you cause all these other problems that no one anticipated when we made these drugs. Okay, I have a million questions, but I'm gonna just cut to the chase. Like, we take these drugs all the time, all of us. Like, should we stop taking these drugs?

No, that's no, I don't want to scare you into thinking like these are evil drugs. They're great drugs. They work really great, but they're not candy. The way we think about it in the hospital as a short, as a quick like thing is like if you're over 65 and taking these drugs every single day.

for months on end, like, see a doctor. Let's figure something out for you. Oh, interesting. Okay. If you're young, like, don't worry about this. If you're healthy, don't worry about this. And in general, don't freak out about this at all. But this is more of a macro scale, you know? Like, I just see there being a vulture-faced reaper who's like, oh, you're trying to avoid pain? Oh, you're trying to avoid death? Like, it's...

Like, like if you, if you, if you budget over here, it's going to budge right back over there, you know? That's how it feels to me as like a doctor. It's very frustrating because, you know, what am I supposed to do? And, you know, I'm, I'm going to keep taking these meds. I'm going to keep giving these meds. They work.

They do help people a lot. But yes, like you said, there's a little cost there. Or, I mean, I guess a big cost if you're one of those unlucky people who gets sick and dies from the drug. Yeah. Or, I guess, if you're a vulture. Well, the vultures are doing okay, actually. Scientists found an alternative drug for the cows and...

And India, Pakistan, and Nepal, they all got together and actually banned diclofenac for veterinary use. Wow. Okay. And the populations of vultures stabilized.

So that's that story. Huh. What does that mean for the Tower of Silence? Is it back? No, not exactly. Because, you know, these vultures only have like one offspring per year. So it's a slow process, you know? Huh. So what are Zoroastrians doing here?

in the meantime, when they lose somebody. So yeah, for Parsis, it's still rough. They started by trying to use chemicals that they would put on the bodies to help them decompose faster. Another thing they considered was putting a big sun glass, like basically think of like a magnifying glass where you like, if you're a kid, you like burn ants with a magnifying glass. Yeah, this feels dangerous. So they're thinking about that.

We have to sit over here. Eventually, I started wondering, well, what about you? When you die, what do you want to do? What does my mom want? Well, since there are no vultures anymore, which I actually think is a great idea, but since there aren't any vultures left, I would prefer to be cremated or the new green burial thing. You know, I wouldn't mind if a tree grew using my body.

But when my mom said that, I kind of thought, like, wait a minute. Like, no. Like, I thought the whole point was that the only way to get to heaven was to go through the Tower of Silence. Oh, yeah. The Orthodox believe that they won't go to heaven if their bodies are disposed off except in the Tower of Silence. But, my priest says... As far as I'm concerned, they're daft. They're nuts. There's no vultures right now. So the Tower of Silence is off the table. My father died in hospital in Boston, and we had his body cremated. He himself had said that, look, if I die, don't have my body shipped back to India. Yeah.

Have it cremated over here. You don't go to heaven or hell depending on how your body is disposed of. I mean, who cares? Once you're dead, you're dead. I mean, who cares? You're sort of a rebellious priest. I'm not a rebellious priest. I mean, I just think for myself. He says he's just being practical, which is what Parsis do. Which is what Parsis do, what they should do. The whole reason our religion created the Tower of Silence in the first place is because it was practical, simple, elegant. And now it's not.

Until the vultures come back anyway. Cool. Thank you. I don't have anything else. You're very welcome. I'm glad to have an uncle that knows everything about everything. Stop calling me uncle for crying out loud. Makes me feel old and decrepit. Contributing editor, Avir Mitra.

That's our show for this week. This episode was reported by Avir Mitra with help from Sindhujana Sambandhan. It was produced by Sindhujana Sambandhan with music and sound design by Jeremy Bloom with mixing help by Arianne Wack. It was edited by a rebellious editor, Pat Walters, who has been known to think for himself.

And to occasionally spit battery acid urine when attacked. Watch out for that one. Special thanks to Daniel Solomon, Heather Natola, and the Raptor Trust in New Jersey, and Avere's uncle, Hashung Mola, who told him about this story over Thanksgiving dinner. It's how the reporting gets done over Thanksgiving.

Mashed potatoes and stuffing and not hamburgers because Avere doesn't eat ham burgers. I'm Lula Miller. I'm Latif. Let us know if you want us to include Vulture poop boots in our next round of merch. That's it. Thanks so much. Thank you, Vulture. Bye-bye.

Radio Lab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design.

Our staff includes: Our fact checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger, and Natalie Middleton.

This is Joel Mosbacher calling from New York City. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox Assignments Foundation Initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. ♪