Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

WNYC Studios is supported by Zuckerman Spader. Through nearly five decades of taking on high-stakes legal matters, Zuckerman Spader is recognized nationally as a premier litigation and investigations firm. Their lawyers routinely represent individuals, organizations, and law firms in business disputes, government, and internal investigations and at trial. When the lawyer you choose matters most. Online at Zuckerman.com.

Radiolab is supported by Progressive. Most of you aren't just listening right now, you're driving, exercising, cleaning.

What if you could also be saving money by switching to Progressive? Drivers who save by switching save nearly $750 on average, and auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts. Multitask right now. Quote today at Progressive.com, Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. National average 12-month savings of $744 by new customers surveyed who saved with Progressive between June 2022 and May 2023.

Potential savings will vary. Discounts not available in all states and situations.

Depending on certain loan attributes, your business loan may be issued by OnDeck or Celtic Bank. OnDeck does not lend in North Dakota. All loans and amounts subject to lender approval.

You hear that? That's the sound of instant relief from nasal congestion by the number one best-selling nasal strip brand in the world, Breathe Right. Breathe Right's drug-free, flexible, spring-like bands physically open your nose for increased airflow, allowing you to breathe easier, one breath at a time. We may not be able to put the feeling of instant relief into words, but believe us, you'll be able to feel it. Ah. Try us for free today at BreatheRight.com. Ah.

Listener supported. WNYC Studios.

Hello. This show we are about to do, it began with a conversation that we had with a friend of ours, Eric Simmons. And he told us about this moment. Yeah.

That was kind of strange. This is the San Jose Sharks, actually, who... Is this a hockey team? Yeah, hockey team. Okay. And I'm pretty strongly identified with hockey to begin with. I play hockey. My dad has played hockey his entire life. And the Sharks started in the Bay Area when I was 10 years old. Sharks are my favorite, favorite creature by a long way. And so I've rooted for them forever. And for the last...

Like six years, they've been really good. Every year they're picked at the beginning of the year to go to the Stanley Cup, maybe to win the Stanley Cup. And every year they fall short. And so in 2007, they were in the playoffs. The Sharks are the top seed. They're playing the eighth seed, which also is Anaheim, which is probably their biggest rival. And they lose. And I remember driving home from the ice rink. It's probably about midnight. And it was a really pretty night out.

Like the city lights and they're like shimmering on the water and there's always these tankers out like parked in the bay. There's like the silhouettes of the boats and the Oakland coastline and the San Francisco shoreline. And like this is everything that makes me happy in the world. Eric says usually when he sees that view, no matter how he's feeling, he's like, okay, everything's going to be good. It's going to be fine because that is one beautiful city.

But that night, I was so angry that I remember noticing this like this like beautiful scene and thinking, I hate this. I hate everything about it. Burn down in flames. Like, that's embarrassing. The fact that these guys that I don't know lost a hockey game in Dallas, that has the power to override everything I think I like about myself and just turn me into this like drooling, savage, angry beast. And I don't like that.

Do you know what I love about that story? Is it's so typical, you know? Almost every sports fan has had a moment where you're like, I cannot believe my own emotions right now. Are you a burner? I mean, do you watch sports? I'm not, no. I mean, I watch sports, but I don't get into that. I don't get into a darkness. I do. There have definitely been times I've wanted to burn down New York. And have you ever asked yourself, like, why? Well, that's the question.

Right? Yeah. For this hour, anyway. Like, why is it that something as trivial as a hockey game can feel like life or death? Which probably doesn't happen to a lot of public radio people, but hey. Well, it could. It could. You shouldn't think that. Yeah, all right. All right. And you know, if you widened the category a little bit and just said games, well, then you'd include everybody. Everybody. So then what is it about a game that makes it more than a game? Yeah. Well, let's find out.

This is Radiolab. I'm Robert Krowich. I'm Chad Abumrad. Stay with us. Sports, to me as a kid, were vital. Sports were, like, if everything else on the planet had disappeared except for sports, I would have been fine. If the church had gone away, if school had gone away, even if all my brothers and sisters had gone away, I liked them fine. But sports was the only thing that I really loved as a kid.

Can you introduce yourself? My name is Stephen Dubner. And Stephen is the author of Freakonomics. Freakonomics. The books, the blog. And I've got my own ISDN line. It's kind of an inside joke. It's a fancy piece of studio equipment because now Freakonomics is also a radio show. Are we talking to you like in your living room? And the reason we called Stephen up, and this is the honest truth, is that Soren Wheeler, one of our producers, overheard Stephen telling this story in the men's room. That's where I do most of my research for the show, actually.

This is where I look for friends. In any case, Sorin overheard Stephen in the stall, got him to come into the studio and tell it to us. Because this is a story about a boy, a hero, and a dad. And how those three things can get a little intertwined. I don't really know what happened. What I know is that when I came into being in 1963,

And Stephen says already at that point, sports was family law. In fact, when it came to baseball, there was even a rule.

to root for the same team. Now, he says his dad actually assigned each of the family members their own baseball team and told them, this is your team. Only you get to root for this team. So my dad was a Mets fan. My mom, I don't remember. But I had a sister who was a Red Sox fan. There was a Cardinals fan, a San Francisco Giants fan. There was an LA Dodgers fan. That was my brother Peter. And I have no recollection of a time before I was a Baltimore Orioles fan. So I think...

What happened is Stevie was born. Here's another kid. We need another team. Who does he get? How about the Orioles? Was this like the tooth fairy sticking a dollar under your pillow? Yeah. How did he assign the Orioles to you? Okay. So first of all, I should just say, like a lot of things in life as a very young, very obedient Catholic boy, I accepted this mystery without question. Okay.

But here's my hunch. My father, I think, felt that it was a shame that he couldn't give more to his children, materially more and even more of himself. And so in my mind, the greatest gift he could give to each of us was our own baseball team. But this is ultimately a story about more than just baseball.

My parents were both Brooklyn-born Jews, kind of typical second-generation American, who before they met each other while they were in their 20s, they both converted to Roman Catholicism. What was the reaction from their parents? Oh, that was bad. That was bad. The way that my grandfather discovered that my father had converted was when some rosary beads slipped out of his...

pocket and fell onto the floor. So it was like my grandfather basically threw my father out of the house, literally declared him dead, sat Shiva for him. And so he says when his dad met his mom, who was another Jewish convert to Catholicism, they were like two refugees who'd found each other. Exactly. Together they left Brooklyn, went upstate, spent all their money on an old farmhouse in the country, leaving behind a past that was toxic.

But then when they got upstate, they found themselves a little out of place. We were these kind of farmer Jewish, Brooklyn Jewish city people who were now upstate Catholic farmer survivor types. We had no money, a lot of kids, and my dad... He said his dad would often be upstairs. Quote, lying down. For hours and hours, which didn't make a whole lot of sense to him at the time. He thought, you know, come on, why isn't he down here with us?

But now as an adult, he understands that his dad was not well. In fact, he was depressed. Really depressed. And how much did you know about your parents' backstory when you were growing up on the farm? Can my knowledge be measured in negative terms? But it was plain to me that my father was a kind of diminished man, that he wasn't capable of doing...

doing all the things that other men were capable of doing. So Stephen says he would go outside to the backyard and spend time by himself pretending to be the Oriole, recreating the games that had been played the day before in real life.

And here comes Frank Robinson. He's still spearheading the Orioles. You know, one game could last me six, eight hours, and I would literally play 162 game seasons. That again makes it too good. I would be every batter on both teams and the announcers. Brooks Robinson completes his home run.

And, you know, this thing about ownership and whether my dad did that on purpose or not, he did make me feel like if they failed, then they needed me to boost them up. And that kept him busy for a while. But then the play happens. And everything changes. To explain, somewhere along the way, when he was 10, Stephen discovers football. Football was considered barbaric. Worst of all, it was played on the Sabbath. Yeah!

But regardless, he fell in love with it. I love the brute force of it. The fact that all these guys wore helmets that made them look kind of like... Kind of like knights. And almost immediately, he latched on to a particular running back from the Pittsburgh Steelers. And that was Franco Harris.

I discovered Franco Harris in his rookie season. Read about him in Sports Illustrated, and from the beginning, everything about him just made sense. I came from a big Catholic family. He came from a big Catholic family. His family was kind of mixed. So was Franco's. His dad was black. His mom was Italian. He was a very unusual guy, very kind of thoughtful and quiet. And I became a big Steelers fan because of him.

Which brings us back to the play. Saturday, December 23rd, almost Christmas, 1972. The Steelers were about to lose to the Raiders. 40 seconds left on the clock. We had the ball on something like our own 35. Last gasp. Hang on to your hats. Here come the Steelers out of the huddle.

Bradshaw drops back to pass. Bradshaw throws, and just as the receiver's about to catch it, he gets crushed. The ball pops up, goes falling through the air.

And right before the ball hits the ground, Frank O'Hara's, his guy, zooms into the frame out of nowhere and catches it in full stride at his shoe tops. That's caught out of the air. The ball is pulled in by Frank O'Hara. Harris is going for a touchdown. Franco runs 60 yards into the end zone. Time runs out. The Steelers win. Shortly thereafter, this play was dubbed the Immaculate Reception. Oh!

You talk about Christmas miracles, here's a miracle of all miracles. For me, as a kid watching it, where my team won and my guy, it was like I was sealed for life. In fact, this guy was so much his guy that when Steve would write his homework papers, he began signing the papers. Franco Dubner.

Wow. And I thought of myself as Franco Dubner, which, I mean, I know it sounds funny now, but it's very natural. Like, we were all named for saints to start with. I mean, my oldest brother was named Joseph. My oldest sister was named Mary. So you're named for saints, plainly. Franco was my saint.

The following Thanksgiving, Stephen's parents drove off to a prayer meeting. It was part of this religious offshoot that they participated in called the Charismatic Christian Renewal. Very fervent group, lots of speaking in tongues. It was strange and a little scary to me to see my parents speaking in tongues. Stephen would sometimes go, but this time he didn't. So his parents drove off to the meeting. In Albany. Kind of far from our house. And a few hours later, only his mother returned. My mother comes home and tells us,

Dad had an attack. She told him in the middle of the meeting, he just fell over. He was in the hospital now, but. He would be out of the hospital in time for Christmas. So that's all I heard. I was a 10-year-old kid. It's like, oh, my dad's coming home for Christmas. Cool. Great. And the football playoffs are coming up.

Month later. It was the 21st of December. Almost exactly a year after the Immaculate Reception. It was the last day of school before Christmas break. It was a half day. We had grab bag Christmas gift exchange at school. Stephen Race is home from school pretty excited. Playoffs are coming up and my dad's coming home and then my mother comes in and says, Dad died. I'm going to go upstairs to lie down. And that, that is when the dream began.

Now, he's not exactly sure if it was that night or maybe the next, but when he went to bed and closed his eyes, this is what would happen. I would go to the VFW Hall in Albany. This is the place his dad had taken him. Where Franco Harris was giving a talk, and I would invite him to come back to my house way out in the boondocks for spaghetti and meatballs. And in my dream, he would come back, he would eat the spaghetti, it wasn't terrible, then I would say, hey, you want to go out in the yard and play some football? And we would go out, and it's dark.

And it's just me and him, we're the Steelers against some other mythical team in the darkness. And we're playing on our field in our backyard and I'm kind of embarrassed because our backyard is all lumpy with frozen cow hoof prints. Because sometimes we'd stake the cow back there. And on the second to the last play of the game, it's like we're behind by three points. Franco would turn his ankle in one of these cow hoof prints and then...

He'd hand the ball to me and he'd say, kid, you have to take it from here yourself. What was the look on his face when he'd hand you the ball and give you the kid's speech? You know Jesus on the cross face? Jesus on the cross. Because he's in pain. He's got a beard. He's kind of sweating and dripping and crying a little bit. And then I'd have to run it in for the winning touchdown. But the dream would always fade there. I never knew if I made it or not. And he says the next night, he had the same dream. Exactly the same.

In the next night? The same. In the next night? The same. In the next night? The same. Almost every night for about three or four years. In the next night? The same. So, you know, I had that dream several hundred or maybe a thousand times. Yeah. And every time you woke up from that dream, I'm just curious, how did you feel? What I remember feeling is that Franco Harris came to see me and that he couldn't

win the game for me, but that he was on my side and he wanted me to win. Kind of period. So if we were to stop this story right now, this would be a story like many others you've heard. Boy falls in love with athlete, dreams of athlete, grows up, leaves athlete behind. But this is a different one. Eventually, after a few years, Stephen stopped having the dream. He moved out of the house, went off to school, got married, became an adult, pretty much forgot about Franco. But then...

Something happens. Purely by accident. Living in New York maybe, I don't know, 15, 18 years ago, I caught sight of him on the cover of Black Enterprise magazine. Franco had become a very successful small businessman, and my heart just started to thump like it had when I was a kid, and I thought, I gotta get to know Franco.

So he tracked down Franco's address. Wrote him letters. Then more letters. And to make a long story short. One day the phone rang and it was him. He did agree to meet with me. I told him I'd like to write a book about a boy getting to know his childhood hero and trying to figure out what that person is like in reality. I was very careful in my mind.

That first day that I met him in Pittsburgh, say, don't tell him the dream. Don't tell him the dream because he will think that you were a freaking lunatic. Right? That first day I told him the dream. I couldn't. It's like, I don't know. What was his reaction? Was he horrified? He doesn't show horror. He's a very interesting fellow. He's got a really interesting manner.

Very low-key. They did end up meeting a few times as Stephen wrote his book, but he says Franco was always really careful to keep him... At arm's length, I would say. And any time they kind of got close, Franco would sort of disappear a little bit. And in fact, toward the end of the book project, they make an appointment to meet. I get to Pittsburgh a couple days early, typical. And Franco's not there. Actually, Stephen ends up standing in a parking lot waiting for him and waiting and waiting.

And then eventually he heads back to New York. And I guess I thought that somehow he had a lot to teach me, you know, about being a man, being a real grown-up, being a father. And he was polite and just not really that interested. And it was around this point that Stephen decided, you know, maybe that's what he was trying to tell me in the dream. And in real life, too. That no one can save you but yourself.

Part of his messiah job was to persuade me that, you know, everybody's got to be their own messiah. That was the message. But isn't that disappointing to you? This guy was your hero. You want him to be all these things, and he didn't want to be those things back. I mean, that must have hurt a little. You know, look, Franco Harris didn't fall in love with, you know, me. He didn't want to be my best friend. But that aside...

He is an exemplary human being. He's a really, he's a good human being. I think you can easily go too far. I think you can put too much of your emotional life in the hands of people who have, you know, who don't know you and have no responsibility for you.

But I think sports fandom is a fantastic gift with almost immeasurable value. Wait, but why? I mean, really? I mean, I love sports, but I mean, he's just a running back. He's not a saint. What exactly about sports gives it an immeasurable value? Yeah.

It's a proxy for real life, but better. You know, it renews itself. It's constantly happening in real time. There are conflicts that seem to carry real consequences, but at the end of the day, don't. It's war where nobody dies. It's a proxy for all our emotions and desires and hopes. I mean, heck, what's not to like about sports? There you go. You just sort of just wrapped it all up in a little bow right there. That was awesome.

Stephen Dubner is the author of Confessions of a Hero Worshipper, and he is the host of Freakonomics. Check them out at Freakonomicsradio.com. We will move on to other heroes, other sports, and other puzzles in just a moment.

Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad. I'm Robert Krolwich. This is Radiolab. We're talking about, well, what are we talking about? Sports. Sports. Games. Games. Yeah, you know what? What we're really talking about is a fundamental behavior of everyone on Earth, including like wolves and cats. Wolves and cats. That was, you're broadening more than I would broaden, but that's, you know, go with it. Well, come on. Like, what do little wolves do? They don't play football. No, but they tussle. Yes. Do you mean like they play? Yes. Like human babies. Yeah. Yeah.

Babies and young children spend almost all of their time playing. Seems so natural we don't even think about it. So let's just go with that thought. This is Allison Gopnik. She's a developmental psychologist. At the University of California at Berkeley. Big sports fan. Yeah. Baseball. Oakland fan. Professionally, though, she studies kids. And she's got an interesting idea. She says if you look at kids, how they play over time, you see that at the center of their play, there's this really interesting tension that exists. Tension of what kind? Well, you can actually hear it.

So we'll get back to Allison in just one moment. Here's a four-year-old girl named Rosa. Listen to her describe her imaginary friend to her dad. And how does Hermione know Antarctica? She was in the Antarctic for a bit before she moved. What was she doing in the Antarctic, in Antarctica? Do you know what she used to keep warm?

To keep what? Warm. Warm? You know what? No. She got leopard seal skin and fur to make a coat. And then put buttons on. And what prompted her to move from Antarctica to the moon? Because she wanted a place higher.

And now she's thinking she wants to move back to what he talked about. In preschool children, you start seeing this wonderful flowering of pretend play. The children are becoming ninjas and princesses and superheroes. And at first, says Allison, this is what play is all about, inventing, making up crazy psychedelic connections, complete improv. You get this period to just explore, just innovate. I jumped from plane to plane.

What did you eat on the moon? House mice. House mice? House mice, of course. But if you fast forward just a couple of years, so not four anymore, but six, six-year-olds, the vibe totally changes because now it's all about rules. If the tagger in the freezer tags you, you're frozen. But then if somebody else tags you, these two are faces, okay? So let's play. She did. And she freezes. Freeze. That's how

With six-year-olds, it just sounds really different. You hear a lot of this, a lot of yelling about what's allowed, what isn't allowed. In some ways, I think the school-age children are practicing being in a society. They're practicing having laws. They're practicing having rules. They're sort of developing a theory of sociology. Yes, I do.

So you got these two modes of play. You got the three-year-old inventor who's like... Okay, I'm just going to make this happen. I'm going to create something new in the world. Then you've got the six-year-old enforcer who's like... You can't just create what you want. The world is bigger than we are. We need rules. And one of the things that's really interesting about the games that seem to stick...

is that the greatest games, like baseball, are games that let us experience the world in both those ways at the same time. In other words, like a good game is a kind of weird, constantly shifting war between the three-year-old in us and the six-year-old. I think she's probably correct because there are games which suffer from a lack of the tension she's describing. There's one game in particular. Okay.

I don't know if you've played it lately, but we heard about it from this guy, Brian Christian. A writer, yeah. He was on a recent show talking about robots, but he also mentioned...

This little... Moment? Yes, it's a moment. So yeah, at the World Checkers Championship in Glasgow, Scotland in 1863, it is James Wiley against Robert Martens. The two best checker players in the world. Wiley, Wiley. Playing a 40-game series. All 40 games opened with the same three or four moves. And all 40 games were draws. Ha ha ha!

Really? Yes. Not only that. 21 of the 40 games are the exact same game. Meaning that move for move for move, they were precise duplicates of each other. Start to finish. Every single move was the same? Yeah. You know, can you imagine? It's like a month of...

How exactly does that happen? Well, see, these guys were professional checkers players. Yes. So they studied moves that other competitors had made. They would write them down, memorize them, and they became a kind of catalog. So at a certain point, every move you saw on the checkerboard, you'd think, oh, yeah, that one. Checkers had hit this point where the conventional wisdom about what was the proper move to play changed.

had gotten to this point where there was now basically a perfect game of checkers and with the world title on the line. Both players played that perfect game over and over and over. They stuck to the script. So this was really rock bottom for the checkers community. Wow, yeah.

So there you go. That's why no one plays checkers anymore. Well, some people play checkers. I play checkers. What? No, you don't. Checkers is fine as long as you don't play it for too long or too well. I mean, if you're a lame checker player, you could play checkers forever. Well, then what's the point? I mean, why would you play a game that's been gobbled up? It's dead. But by the way, this thing that you just said killed checkers? Yeah. This concept has a name. It's called? Called The Book. The Book.

The danger is that the entire game stays in book the whole time. And that danger, says Brian, is not specifically confined to checkers. Occasionally, very rarely in the chess world, you'll see two grandmasters play the exact same game that another pair of grandmasters played, you know, a year before. And they'll get boos and jeers all over the internet as a result. Now chess, let me talk about chess. The book in chess...

is huge. It started in the 16th century and for hundreds of years players were keeping track of moves and counter moves and counter counter counter counter moves until by the 1950s... It was like a library. It actually was a library. In the Moscow Central Chess Club. And who is this? This is Fred Friedel. He's a chess analyst and one of the few non-Russians to have seen this room. Yes, it's a huge musty room.

All these shelves, and there were little boxes, and the boxes contained little cards, index cards. And each of these cards documented a particular game of chess from the past. And for a while, this was all a secret. There were about three or four players in the world... All Russian. ...who had access to... When one of these guys had a big game, they would go to this library and say, all right, I've got this opponent, he's a Polish guy, Przyspiorca, something or other. Give me all his games. Get up!

And suddenly you have a few hundred cards. Which you and your team could study. This is how they prepared. By memorizing literally thousands of moves. Tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands. But where Fred comes in is in the 80s. He convinced the Russian Federation to put this online. Where anyone could study it and add to it. And suddenly this book explodes. Which is for some people amazing.

People tend to boo me sometimes when I come into a chess tournament today. They will point to me and say, that's him, Frederick, the man who ruined chess. Because here's the modern game. When two players sit down at one of these tournaments to face off, they've already consulted Frederick's database, which he's named Fritz. The chess players all call it Fritzy now. And because of Fritzy, they walk into these games with so much of the book in their heads that whole portions of the game are...

Very checkers-like, very rote. You'll see this if you watch grandmasters play speed chess. That's Brian Christian again. They'll just hammer out the first dozen or so moves. Bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. With barely any thought. Out of memory, it used to be two, three, four, five, six moves. No big deal. Nowadays, it is 16 moves, 20 moves. There does seem to be a kind of creep that's happening. The book is getting bigger and bigger and bigger.

But inevitably, in every chess game, there is a moment which puts the book in its place. And if you watch a game, is there a chess tournament coming up, like a big one? Yes, next Thursday I'm going to Romania where some of the top players are playing. If you watch a game, as I was able to do, because you can watch these games online. Okay, yeah, we're going to watch a chess tournament online. You will see that moment. And it's not like, you know, Jordan scoring 40 points while he has a fever. It's not like that. But if you know what to look for,

It's quite profound. Okay, it's 8.30 a.m. I'm here with my little man. Say hi. Hi. And somewhere in Romania, two grandmasters are about to sit down at a table to do battle, and I will watch it virtually. Hello.

The match I watched was Magnus Carlsen, the world's top player, versus Hikaru Nakamura, the U.S. champ. I call up Frederick. Hello, it's Frederick. To give me the play-by-play, because I actually don't know much about chess. Okay. Well, his program, Fritz, can tell you how many times each move has occurred in the entire recorded history of chess.

What does that mean? It's like his computer can look at the board and say, ah, that move you just made, that has happened before, and I will tell you exactly how many times before. Hey, it started. Here we go.

Move one. White moves its D4 to D5. White pawn two squares forward. My database tells me that there are 1,775,000 games in which this occurred. Then move two. Black counters with its pawn going from C4 to E6. Now we've got

two pawns facing each other, middle of the board. And according to Fred's database, this exact configuration has occurred in 514,518 games. So, a million and a half down to half a million? Smaller. Yes. Move three. White moves another pawn. 335,000. Black, another pawn. 149,000. Even smaller. Yep.

White moves its knight. 114,000. Black moves its bishop. 91,000. Less again. White pawn takes a black pawn. Just have our first casualty people. 2,428 games. What was that again? 2,400. Oh!

The black pawn responds. 2,613 games. White bishop flies across the board. 2,125 games. Black moves another pawn up. 1,200. White queen does a little thing. 381 games. 381. Getting lower. Yes. Black bishop retreats. 19 games. 19. 1-9. White moves another pawn. Which has occurred in 11 games.

Okay, black bishop retreats. White bishop advances. Ten. Black bishop falls back even further. Black bishop takes white bishop. White pawn retaliates, taking black bishop. And then, white rook and white king switch places. You have a position which has never occurred before in the universe. Ever?

No. In the universe? Not in the history of this universe. And this is what is known as the novelty. The novelty? The novelty, yeah. And in chess notes, if you read chess notes, you will see... That shortly after this move... The annotator writes, out of book. Out of book. Yeah, out of book. Bye-bye book. Which means... No more book.

Both sides now are on their own. And everyone we talked to who plays chess told us that when you get to that moment, you feel you're alive.

in a way that you're not normally. That's Frank Brady. He's an author and a professor at St. John's. An international arbiter of the World Chess Federation. You're totally in it. Your mind is in some ways not even operating. It's like you're back to being three again. What are you saying? I'm saying this is one of the reasons we watch sports for these kinds of

Zero moments. A position which has never occurred in the universe. At the same time, the zero is happening inside all of these rules which are like our lives. And this is what Allison was saying. Games let us experience the world in both those ways at the same time. The Pacers confound.

For example, here's one. 1999 Knicks Pacers. Larry Johnson has the ball. Knicks are down by three. Final seconds. He has no shot. Best you think he could do is tie, but he has no shot. And then somehow he twists, he shimmies, he moves to the left, throws it up. Johnson is fouled. And hit!

That was like, what? What? I mean, that's in the rules, but nobody could have imagined that. A position which has never occurred in the universe. I mean, I don't know about never, but... You want to know mine? Sure. This is a hockey moment. It's Wayne Gretzky, early 90s. He's playing, shoots for the goal. The puck hits something, somebody, and starts flying through the air like a tennis ball. Wayne Gretzky turns around and whacks the flying puck out of the air.

And up in the air, Kresge scores! What a shot by Wade Kresge! Just smacked it out of the air? Yep. Smacked it out of midair! The universe would have to be extremely old to have a previous version of that. Frank, do you have a number one favorite novelty in chess? Well, my number one favorite would be Bobby Fischer's Game of the Century. And when did that happen? We're jumping to 1956. 1956.

Bobby is 13 years old. And is he the Bobby Fischer of legend at this point or just a 13-year-old kid? He's a 13-year-old kid. He got invited to this tournament. It was an all-adult invitational tournament. And Frank says all the world's best were there. And this was kind of Bobby Fischer's first –

official match in the big leagues, so to speak. And to set the scene, it was October. Warm Indian summer. We're at the Marshall Chess Club in Manhattan, which is this big, stodgy brownstone with lots of mahogany. And Bobby Fischer, in his t-shirt, sits down to play a fellow named... Donald Byrne.

A guy who looked the part. Very urbane, sophisticated. Jacket, bow tie. He always had a cigarette between two fingers. I imagine it would have been hard for him to take this kid seriously. Yeah, and he was not doing all that well. From the beginning, Bobby Fischer was making what looked like dumb errors. He was losing.

For example, midway through the game... Bobby made this move where he moved his knight to the rim of the board, which is usually, strategically speaking, is not the greatest place to move your knight. Because, you know, if your knight's shoved against the edge, it's boxed in. And the knight could be taken. And people said, what? What is it? Did he blunder? Come on, kid. Yeah, this is crazy. But then, Bobby Fischer does something truly crazy. What? He does something.

He leaps so far out of the book, in effect, that people are still talking about this move 50 years later. On the 18th move, he allowed Byrne to take his queen.

He just said, here, take my queen? Now, in chess... That's like crazy. Yeah, in chess, it's almost impossible to win a game if you lose your queen. It's like, what? That's got to be wrong. There must have been a stupid blunder. It seemed like maybe he was throwing in the towel. So a crowd gathered... A scrum of people hanging around. ...to watch this kid get put in his place. And Byrne did what anyone would do in that situation. He took the queen. But...

Just at the moment you would think he would have Bobby Fischer in a stranglehold, he was chasing Byrne all over the board. 20 Moves Later

Byrne was done. Nothing he could do. He was checkmated. And Frank says if you analyze the game, you see that it all began and in a way ended when he sacrificed his queen. It was a lost game from that moment. If Byrne didn't take the queen, he was lost.

If Byrne took the queen, he was lost. Wait, are you saying he essentially checkmated him 20 moves ahead of time? Yes. It was unstoppable. It was forceful. So it's like he wrote a new book. He stuck the guy in his book. I love that. So it's kind of interesting. You can start the game in book, so to speak. And you're kind of locked into a set of moves. The game ends. Kind of the same way. Same way. That's destiny. But then in the middle, you just get a peek.

at something... Infinite. Infinite. Although we were wondering, like, is that middle space really infinite? I mean, we asked Frederick if people played chess for hundreds and hundreds of years, inventing new moves into that empty space, would they ever fill it up? And he said... No, because the number of chess games that are possible is vastly more than the number of atoms in the universe.

That is a silly little number compared to the number of chess games. What kind of a number is that? How many atoms are there in the universe? 10 to the power of 82 the last time I counted. No, 78. 82 zeros. 10 to the power of 78, I think is more accurate. And there are more...

Possibilities within a 40-move chess game? 10 to the power of 120, approximately. And he says if he were to try to get all that information into Fritzy, his database... We would have to dismantle an entire solar system just to store the information. And he says you'd have to dismantle another one just to plug it in. ♪

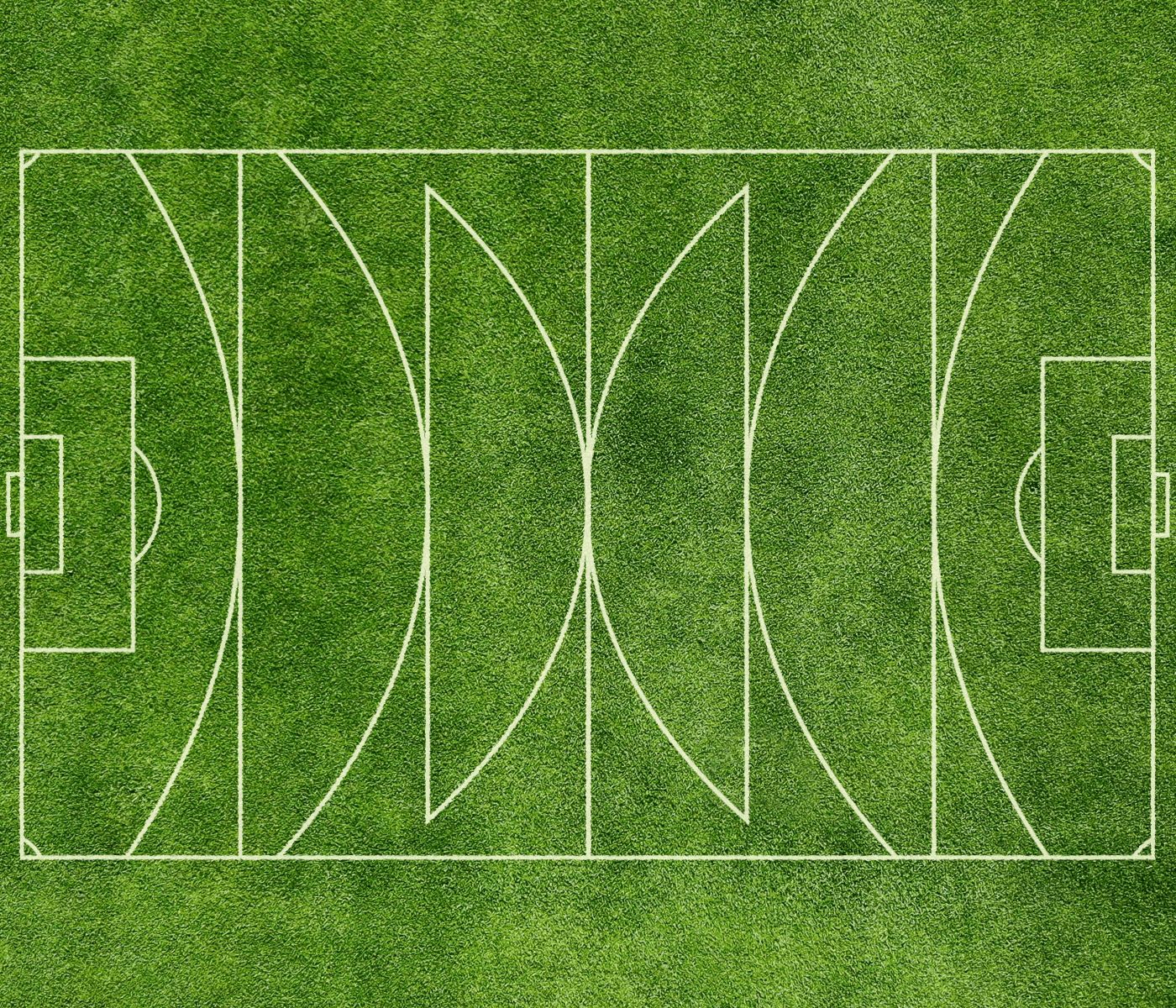

And what he says about chess, you could say that about hockey, you could say that about baseball, you could say that about curling. But you could not say that about checkers. Let's just be clear. Checkers aside, every game has this kind of strange thing. It has a field of play. A small little box. It could be a board, it could be a field, whatever. And then you step into it and there's like a... A solar system. A solar system.

Thanks to Alison Gopnik. She wrote the wonderful book, The Philosophical Baby. And Frank Brady, who's the author of Endgame, Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall. And also Brian Christian, who wrote the book, The Most Human Human.

Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad. I'm Robert Crowley. This is Radiolab. That was the Tarantella opening, a little hey that we can get. Oh, was it a little? No, it was fine. Was it good? It was good. I like the Tarantella. I can bring it down. No, no, no. We keep going. So we're talking about sports. And games. And emotions. And we just did a thing on rules and creativity. And now it's time to add yet another element to the mix. Because what do you get if you put all those three things together? You get. You get. Bring it. Do it. Say it. Yeah.

You're a little energized here. You get a story. Exactly. Really good games are sort of story generating machines. For example, here's Alison Gopnik again talking about a little teeny story that happens dozens of times a game in her favorite sport. One of the great moments in baseball is always that that ball is going out there and the guy is going out there with the glove and it might end up in the glove and it might not and he backs up against the stadium wall and he's

he gets it or he doesn't. That wouldn't be nearly as much fun if he was just playing catch, right? That's a fantastic human drama. So the question we want to explore now is what kind of drama do you want? What kind of drama to you is most fantastic? I think you want the headphones the other way around. That's our producer, Soren Wheeler. How's that? Something like that. Who's out of the bathroom and seems to have made a new friend.

So set that up. Who's that guy? So that's Dan Engberg. Senior editor at Slate Magazine. And I brought him into the studio because he told me about this thing that had happened to him. When I was watching the NCAA tournament. The basketball. Men's college basketball tournament. This was just last year. And I don't know anything about college basketball. I have two or three sports that I can pay attention to. Some people have one or two or zero. But college basketball isn't one of them.

But there's this tournament on every year. It's kind of exciting. So he watches. Yeah. And what he does, since he doesn't really have any loyalties, he doesn't know who to root for. He just kind of, by default... I just pick whichever team has the lower seed.

Whichever is the worst team. Why do you do that? I have no idea. And it came to a head when I showed up at a friend's house and they had the game between Butler and Michigan State on. It was a semifinals. And they were both seated number five. So it's like your little system is... Right. I have no idea which team to root for. So I just was, I started rooting for whichever team was losing. And it was a close game. So... Butler would make a run.

Then Michigan comes back. I start feeling sorry for Butler. Every time one would go up, he'd switch to the other. And at a certain point, he's like...

Wait a second. This strategy guarantees that at the end of the game when the buzzer goes, I'll have been rooting for the team that lost. Right. I've actually created a situation where I'm guaranteed to be disappointed. You're guaranteed to be disappointed. So Dan decided to figure out like, what the hell is going on? Why? Why would anyone do this to themselves?

Is that something that's actually been studied? Yeah, so there's a small group of psychologists. That would be me. And me. Who are interested in this question. Underdogs. Tracked a couple of them down. My name is Scott Allison. Nadav Goldschmidt. Two. University of Richmond. University of San Diego currently. So there are these studies that are just...

sort of hilariously simple where you take a bunch of undergrads and you put them in a room and we give them scenarios to read like a paragraph involving say two competing teams and there's almost no information the teams don't even have names it's team A and team B team A is playing team B in a game

You don't even have to tell them what sport. Team A is considered the better team and is more likely to win. Who are you going to root for? 80% of the students choose the underdog team. 80? Yep. In fact, a lot of times it comes out 90%. Nine out of 10. Yes. In the absence of any reason...

to choose one or the other. That's almost universal. You can do this study in all different ways, and the answer always comes out the same. You can describe it as two political figures. You know, running for election. Or you can talk about two businesses. Mom and Pop's electronics store against Walmart. Or you can talk about two landscape painters who've painted pictures and are now trying to...

landscape painters? Yes. We gave participants a painting. Half the participants were told this painting was done by a successful, established artist. You know, Soso, who has a gallery show downtown. And the other half of the participants were told this same painting was done by a starving artist. First year art student. Who's trying to make it in the art world. Who only has one arm. Yeah, exactly. And people have this very strong bias in favor of the underdog painter. So what else do we have? We got landscape

painters. Yeah. Unnamed sports teams. Businesses. Politics. And my favorite, shapes. Shapes. Yeah. What would an underdog shape be? It's just a circle about an inch in diameter moving left to right across the computer screen. Moving up what could be a hill. Exactly.

As the circle moves up, the circle slows down as it goes up the hill. Nudging up and then dropping back a little bit and then nudging up and dropping back a little bit. Quivering. Yeah, yeah, yeah. And then along comes... A second circle that has no trouble getting up that hill. Okay.

Cruises past this low poke circle. Zooms right past it. And sure enough, people have a real preference in some way or another. They're really rooting for circle B. The struggler. We get people emotionally reacting to a geometric shape. When they're sitting there, are they like, come on, come on, you can do it. Yes.

Yes. You're pulling for it. It's going to be like Rudy, you know. This is how deeply ingrained the underdog phenomenon is in us. At this point, like my question is, why? Why? Exactly. Why do we do this? Well, um. Well, I. Well. Well, I think that there are two different approaches to that why question. One of them is this kind of what they call an emotional economics argument. And it goes like this. If you know that you have an underdog and you have a top dog. So the top dog is expected to.

to win, right? If you think of this like the way a gambler would think of it, like if you go with the top dog, they're expected to win, so you're not going to get a big payout if they do win. Minimal emotional payoff. But you'll lose a lot if they lose. Meaning you won't feel too good if they win, but you'll feel really bad if they lose. Yes. But if you go with the underdog... It's the reverse. Right. They're expected to lose. So if they do lose, it's not that big a deal because you kind of figured that was how it was going to go. But if they win...

You feel great. A significant emotional payoff. So it's like betting on a long shot horse. You can put in five bucks, you're probably gonna lose it, but if you win, you might get back like a hundred. Exactly. Hmm.

I don't think... That just does not feel at all like how I watch sports. Well, there's another argument, which is these guys say that maybe it's something about fairness. Deep down, we want to live in a fair society where there's an even playing field. And there's research that shows that fairness is a pretty deep instinct in us. But I don't know. I mean, like, none of that seems to... I guess...

The thing is that this whole thing feels like a lot more basic. If you look back at like the stories we tell, this underdog story is ancient. The Iliad, the Odyssey, great epics from Asia, Africa. That's all the same story. And so Scott says, you know, maybe we love the underdog because we feel like we are the underdog. I mean, in some sense, just to be a living thing is to fight against the odds. Think about newborns.

You can't be any more weak and helpless and small. You know, I mean... The baby. I guess that's true. But I don't know. I mean, I don't remember being a baby and feeling like... But I do remember junior high.

And I do remember feeling like I would never get a job. And I do remember feeling like there's no way that girl's ever going to like me. We need these stories just to make it through. They're part of who we are as human beings. There's actually a very interesting...

about Haruki Murakami, the famous Japanese novelist. Yeah, author, yeah. He was awarded the Jerusalem Literature Prize. And this was in the midst or immediately after Israel invaded Gaza and there were more than 1,000 Palestinian dead. In his delivery speech, he said the following...

Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg. No matter how right the wall may be and how wrong the egg, I will stand with the egg. Someone else will have to decide what is right and what is wrong. Perhaps time or history will do it. But if there were a novelist who, for whatever reason, wrote works standing with the wall, of what value would such works be? What value would these works be?

It's an interesting word. It's almost like he's saying a story's job is beyond morality, it's beyond truth. Its job is somehow to tell you that the world could be a way that we know inherently it never will be. I think that's what he's saying. Or maybe he's really saying that I stand with the powerless...

And the powerful can take care of themselves. So what I'm going to do is I'm going to add a little weight to people who have no muscles of their own. I'm going to put a little pebble on the scale. That's the job of the story. And I guess if the scale is always weighted in the wrong direction, then that's why we love this story because we need more pebbles. Well, yeah, but there's a question we haven't asked here. Which is? Well, four out of five of us root for the underdog or the struggling circle, but that's not everyone. ♪

One out of five people are like, screw that circle. I'm excited about the circle. You could probably do some interesting follow-up studies on like... Who are those psychopaths? Yeah. I see you assume they're psychopaths. I do. Actually, oddly...

We ended up bumping into a guy who falls into this group. It's Malcolm. Yeah, hi. His name's Malcolm Gladwell. He's a writer. For the New Yorker magazine. He's also written a bunch of best-selling books. And in the middle of a conversation, unbidden, by the way, he suddenly says... Oh, I never ever cheer for the underdog. You don't? No. No.

Why? Why not? Because I'm distressed by the injustice of the person who should win not winning. The injustice of the what? Losing for the favorite. That is the most exquisitely painful situation to be in. So I remember as a kid, the first time I ever ran, I was a huge track and field fan. 76 Olympics.

Dwight Stones lost the high jump, even though he was so far and away the greatest high jumper in the world, because it rained. His technique required absolutely perfect footwork, and he would slip on the tarmac. And I just remember sitting there as a kid, and I was just devastated because I could feel his pain.

And his pain was so much greater than anybody else's. What's wrong with you? It's too painful if they lose. When Dwight Stones loses the high jump, it is literally one of the most painful experiences of my young life. I thought about it for weeks afterwards. I just couldn't wrap my mind around how he must have felt going home.

And ever since then, I was like, there's no way you could not cheer for the overdog because they will suffer. I mean, it's the only humane position because you were trying to end human suffering. This is as tortured and twisted the logic as I've ever heard. I mean, I always thought this was some rare evidence of my empathy that I felt. I'm so sorry to have brought you the news. Exactly. There's another part of this too, and that is that it is that I have a desire

a deep distrust and unhappiness with luck. So I do not like it when the outcome turns on an unrepeatable sequence. So Georgetown losing to Villanova in, is it the 82 NCAA college basketball championships? There is no way, you could play that game

100,000 times and Villanova would still only win that one time. That just, that game, it did more than upset me. It outraged me. I mean, I just thought, this is not, it's just not right. It is like a, it is a violation of everything. You shouldn't be able to shoot 78% from the floor or whatever the, I forgot what the number was. The preposterous number they, they,

And I just, you know, if I had been on Georgetown, I would wake up every night in a cold sweat to this day just thinking, this is outrageous. Like, how did this happen? That's so weird because you're a storyteller by trade. Like, what if Hans Christian Andersen had woken up every morning and said, here, I have a great story. There's an ugly duckling and it just stays ugly because, you know, why should it get lucky and be a swan? It's just an ugly duckling. We're not talking about stories. I understand stories.

To me, a game is not a story. To me, a game is it is a contest between two parties according to certain rules and when the when expectations and rules are violated, some part of me takes offense. Well, I'm curious, how do you feel about the the people who always root for the underdog, which happens to be most people? Do you feel like that's the weaker position morally? Is it weaker morally?

I mean, there's a very unflattering interpretation of this. And that is that on some deep level, I think of myself as a favorite, not an underdog, right? You know, that's like I say, that's an unflattering way of interpreting my motives. But you know, unlike many of my peers, I grew up in a tiny, tiny town and went to a kind of an exceptional high school where everyone left at 16 to go home and milk the cows. So it was like a situation where I did sort of grow up as the

If you had parents who'd gone to college, you were the overdog in my universe growing up. So I do sort of, when I was in seventh grade and someone got a better grade than me, it was outrageous to me, right? Because no one should get a, only my friend Bruce should get a better grade than me. He's the only other person in the class whose parents

parents went beyond the ninth grade or who had books at home or who had left the province of Ontario. So maybe there's something in that, that if you grow up in these impoverished environments where you're forced into a particular dominant role, right, you just, you come back to it again and again long after those circumstances have changed.

That's Malcolm Gladwell, defender of winners everywhere. I do. I do hate when winners lose. It is true. It is true. Radio Lab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design.

Our staff includes: With help from Andrew Vinales. Our fact checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger, and Natalie Middleton.

Hi, this is Beth from San Francisco. Leadership support for Radiolab science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, Assignments Foundation Initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

NYC Now delivers breaking news, top headlines, and in-depth coverage from WNYC and Gothamist every morning, midday, and evening. By sponsoring our programming, you'll reach a community of passionate listeners in an uncluttered audio experience. Visit sponsorship.wnyc.org to learn more.