Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

WNYC Studios is supported by Zuckerman Spader. Through nearly five decades of taking on high-stakes legal matters, Zuckerman Spader is recognized nationally as a premier litigation and investigations firm. Their lawyers routinely represent individuals, organizations, and law firms in business disputes, government, and internal investigations and at trial. When the lawyer you choose matters most. Online at Zuckerman.com.

Radiolab is supported by Progressive Insurance. What if comparing car insurance rates was as easy as putting on your favorite podcast? With Progressive, it is.

Just visit the Progressive website to quote with all the coverages you want. You'll see Progressive's direct rate. Then their tool will provide options from other companies so you can compare. All you need to do is choose the rate and coverage you like. Quote today at Progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Comparison rates not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy.

♪♪♪

Listener supported. WNYC Studios. Hey, it's Latif. We pulled an episode from the archive today because it takes on a question that is as pressing as ever, maybe even more so. How do you fix the world? How do you change things when you don't personally have the power to change them? And the people in power don't really want to change them. When all you have is your voice and your life and your love.

What can you do? And I don't mean it in like a, what can you do? I mean it in like a, what can you do that will help make things right? A couple of years back, our reporter Tracy Hunt took on this question by looking at different kinds of AIDS activists in the 80s and 90s. What they did, what it accomplished, where they fell short.

Also, you will no doubt recognize the gravelly and calm voice of Anthony Fauci in this episode. After nearly four decades heading the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, he is stepping down this month. So we wanted to replay this as well to mark that.

Once again, this episode is reported by the super talented Tracy Hunt. You can also hear her terrific work on shows like The Experiment, Notes from America with Kai Wright. This episode first aired back in 2020 and it's called The Ashes on the Lawn. Before we start, just letting you know there is some explicit language in this story. Wait, you're listening to Radio Lab.

Hello, this is Radiolab. I'm Lulu Miller, and today we have a story from reporter Tracy Hunt. Where does this story start? So I'm going to start you off in New York City. June 25th, 1989.

It was the gay pride parade, but it was also the very first time that David Robinson ever laid eyes on Warren Krauss. I noticed this guy I thought was incredibly hot marching by with a group of people. He was shirtless and muscly and he had blonde hair, but it was buzzed like really short. Mm-hmm.

except these two, like what Wolverine had. Okay. They're almost like these little wings up there. He just looked amazing. I remember just thinking, oh my gosh. But you know, he was marching by with a group of people and I remember thinking, oh well, I'll never see him again.

But the next day, David was at an AIDS activist meeting. And who should be in the front row but this guy. Oh. So, yeah. And he invited me to have lunch with him the next day at the apartment where he was staying. And I did go over there. And we didn't, in fact, have lunch. But we had.

had a lovely, lovely time. Right away, David was like, okay, this is it. You're the one. He had grown up on a small dairy farm in Connecticut. It had been a very joyless and sometimes abusive upbringing. He was kicked out at 17 for being gay. And he ended up having his own, gosh, I don't know, just unique way of being in the world. So...

It's a little hard to talk about because I feel he got cheated so, so badly. Warren had told David when they first got together that he was HIV positive. And it was less than half a year after we moved down to San Francisco that the infections started coming fast and furious. By the last, you know, several months,

months of his life. He was just, you know, pretty much homebound. Last two months, he had dementia. The last thing he got ended up causing dementia and he was in the hospital for much of that time. I took him home. His last months until he had dementia, he was really angry.

David and Warren would sit around their apartment talking about that anger and talking about the fact that they both knew Warren was going to die. You know, we would talk and he would express that it was his wish to, you know, make a difference beyond his death. Warren died April 1992. You know, this is a moment when the AIDS epidemic had been going on now for about 10 years and

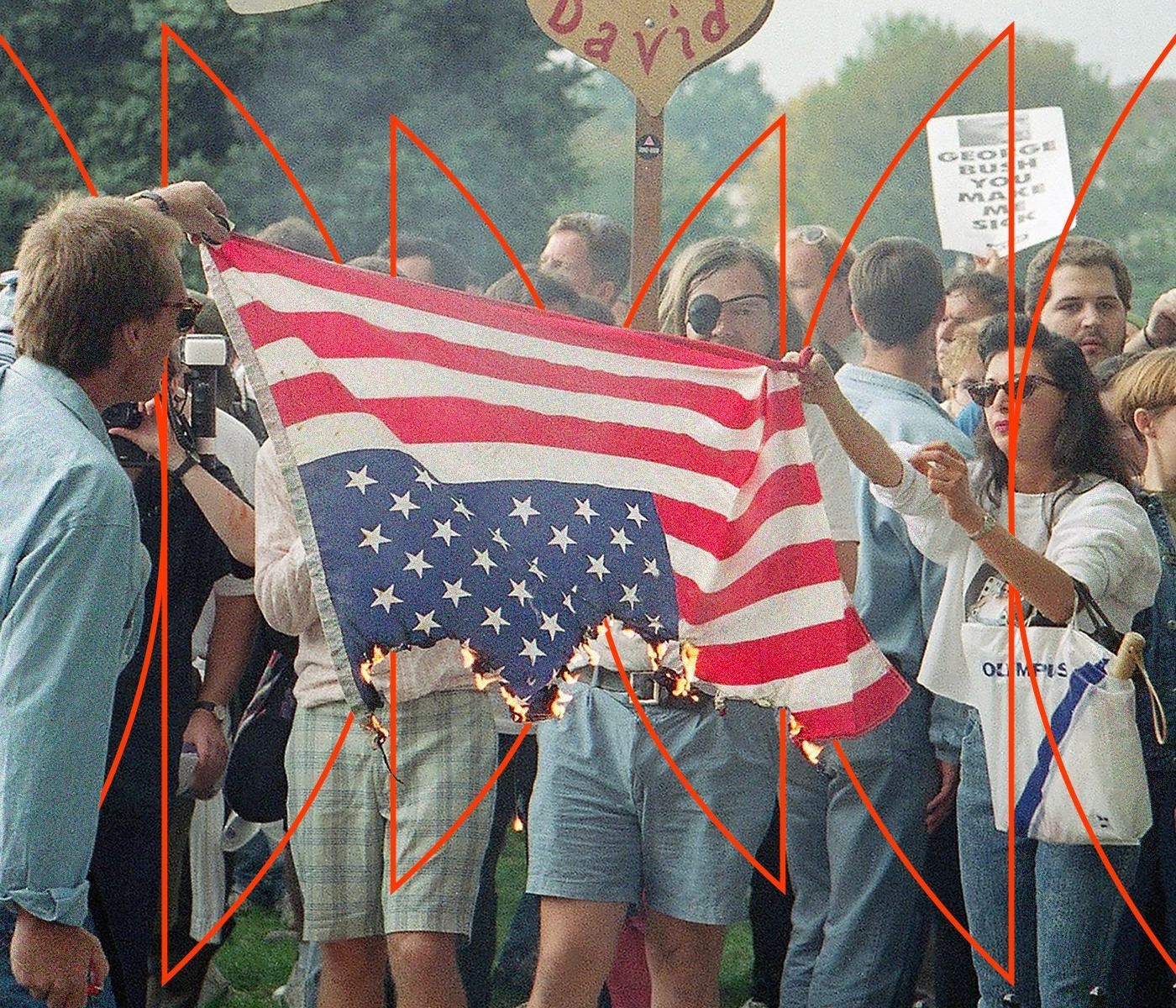

Research into treatments had basically stalled. There was no cure in sight. More and more people were getting sick and dying. We are in the middle of a plague. And it looked like the Bush administration was just not paying attention. 40 million infected people is a plague and nobody acts as it is.

And people like Larry Kramer, who co-founded ACT UP, an activist group that David was a part of, they were at their wit's end. We are in the worst shape we have ever, ever, ever been in. They had spent years protesting and demonstrating and just trying to get people to pay attention, trying to get the government to just do something. Nobody knows what to do next. And that was David's question, too. What do I do next?

What would Warren want me to do? He wanted to be able to continue to make a difference even after he died. And so David was sitting in their San Francisco apartment alone with a box of Warren's ashes. And inside was just, you know, the plastic bag with the ashes and bone chips. And eventually he decided that he needed to use what was left of Warren's body to make people pay attention.

So in October of 1992, David and about 150 other people, many of them members of ACT UP, met in D.C. right in front of the Capitol. You know, I remember lining up

with these other people and some were people I knew very well from ACT UP and some were people I had never met. I mean, it was so visceral. Shane Butler, a student at the time. The drama and the people. I remember it being hot. Alexis Danzig, she had lost her father to AIDS. And the crunch of the gravel under our feet as we walked down the mall. I started marching down the path along the DC Mall.

And as they marched, they started to chant. We're bringing our dead to your door. We won't take it anymore. One of my strongest memories is just of how sore my throat was. I lost my voice and just pushed through it. I was in a line of people who were carrying their beloved dead.

person's ashes in a variety of different kinds of vessels. Some had ashes in a baggie. What was your ashes in? I had created a box. It was painted black with gold line drawings on it. And then for like the last section of the march as we were getting closer to the White House,

I just remember almost a grim feeling. And as the White House came into view, they could see a line of mounted police. The police had prepared by showing up on their horses. 20 feet away from the White House gate, surrounding the entire perimeter of the White House. When you look at videos of this, it's terrifying. There's these cops, like, high up on their horses, and it looks like the horses are going to stampede them or something.

But the protesters had a strategy. The Romans called it the cuneus, the wedge. They formed a triangle with a couple people up in front pointing directly at the mounted police. Behind them were all the people carrying the ashes. All you got to do is get the front of the triangle through the straight line of the enemy and they begin to turn around to see what's happening.

The protesters got the tip of that triangle between two of the mounted police and pushed through. And that gave everyone else an opening to get through. The line of us, the people of us who had ashes, to get right up to the fence. You know, all of a sudden, I remember being at the fence. Physically crammed into one another as we all tried to get as close as possible. Things became very quick and very slow all at the same time.

The people with the urns began to hurl those ashes onto the lawn. I remember opening this box and reaching in and the feel of the bag and turning it over and shaking it. I shook the box out. And feeling, seeing these ashes. This wave of ash in the air.

Some of them just falling and some going in the wind. Lofted back over us and began to coat us. And some getting on my arm. The feel of those ashes, even the taste of them on your face and lips. I can remember having to clean my glasses because I couldn't see. And it was somewhere in the process of this that I went from that grim feeling to just this, just fierce. I'm feeling like an embodiment of enraged grief.

this incredible release of energy out into the universe. Wow. God, I had never heard about this. Yeah. I didn't know this happened. Yeah. I think when I first heard this, I think the dominant thing that I was like feeling and thinking was, that's so metal. Like it's so, like I just, I can't think of a like more pure response to this.

That sort of anger and that disgrace. But at the same time, you know, it just didn't... There wasn't any meaningful response from the White House. It didn't get a lot of media attention at the time. And I think if you weren't in D.C. that day, at that moment, you probably wouldn't have known that it happened. Man, it's like how...

wow, do you have to, like, what does it take? And honestly, that's the thing about ACT UP, the group that David was part of that made the ashes action happen. Because when you look at all the other things that ACT UP did, they're just constantly trying to punch through and get people to see them. Like, for example, they did this die-in at St. Patrick's Cathedral. What did that look like? This is Jesus Christ. I'm in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral on Sunday. We're here reporting on a

Some of the people I talked to, they said that the plan was go into St. Patrick's Cathedral, just lie down like they were dying or dead, you know, simple, quiet. But some of the protesters went off script. Someone smashed a communion wafer. Someone else started heckling the priest. And unlike the ashes action, this one got a lot of attention.

but not good attention. When people from ACT UP started standing on pews and screaming, it really alienated the people who were praying. I saw people get very angry and upset. You know, when I learned this, I couldn't not think about all the protests that happened in the wake of George Floyd.

You know, coronavirus is happening. There's this expression of the grief and anger that people are carrying with them. There are all these conversations about, you know, what is the right way to protest? Can a protest actually hurt the movement that you're protesting for? Like by being too just extreme? Yeah, or like too in your face or, you know, I just...

And I know I'm not really supposed to wonder this because I'm a journalist and, you know, journalists are just supposed to cover these sorts of things. But, you know, I feel like any citizen or activist or anybody has this question in their heart, which is like, what would work? What would make, you know, how do you make change? And I'm.

The amazing thing about the early AIDS movement is that there were so many different kinds of protests going on that it's just like this perfect little petri dish for this question. What do you mean? Well, okay, so just to get started, let's go back to that very same day that the active activists were doing the ashes demonstration. Shame! Shame! Shame! Shame! Shame!

Because right next to where they were marching on the mall, there was another AIDS demonstration unfurling the AIDS quilts. Gary Barnhill. I've heard of that one. Yes, yes. David Calgaro. They did these showings of the quilt, you know, every few years. James Martin Case. That day in 1992, there were...

Paul Castro. 20,000 of these three-by-six-foot sections of quilts. Bill Cathcart. Bob Greenwood. That had Barbie dolls and leather jackets and soccer trophies. Douglas Lowry. All these mementos of people that had died. Felix Velarde Munoz. There were no speeches or anything like that, just...

People reading names. Each person with their own patch of quilts. Made by family members or loved ones. Raymond Case.

You know, you think of your grandmother taking care of you when you're sick. You think of chicken soup and tucked in bed. So I ended up talking to Mike Smith. My name is Mike Smith. I'm the co-founder of The AIDS Quilt. He was there from the beginning. And he told me that when the quilt first started...

It also came from an angry place. If you back up to its inception, many of the earliest panels were made out of anger and desperation. Probably the best known of the angry ones is literally white vinyl with red oil paint. And the red kind of ran down in drips. Along the bottom, he says, Ronald Reagan, his blood is on your hands.

But then about four weeks before the display, we'd had some coverage in The New Yorker and a few other places. Mike says right before the display in 1987, they had been putting out newsletters and doing all kinds of press. We'd said, if you get us a panel by September 15th, we would get it into the event on the mall a month later. And on the three days around September 15th, we had 800 pieces of overnight mail. Oh, wow. From every state. Wow.

And they weren't from the gay men in the urban cores. They were from mothers. It was all these like Midwestern ladies whose...

sons died of AIDS and they had no one to talk about it with. They couldn't really talk about it maybe with their families. They couldn't even tell their church group what their son had died of. First of all, how much, how isolated and desolate do you have to be to create a beautiful, loving fabric memorial for your son and then box it up and send it to a bunch of gay men you don't know 3,000 miles away? But we tapped into this

nationwide sense of grief. And that's when the panels he was saying started to get really, really beautiful. Bomber jackets and high school track medals and things that mom put on that really tell the story of the person. And it changed everything. By the time we got the quilt out there on the mall, this wasn't a protest banner. It was literally all of America saying, wake up, our sons are dying.

You know, when it came to talk about media attention, there was like a ton of media attention on the AIDS quilt. Good morning. It's sunrise here in Washington, D.C. I'm at the Capitol Mall where the NAMES project AIDS Quilts is to be unveiled. A quilt, a dark reminder of AIDS and its victims was unfurled. Each panel representing a death. And it cracked open some political movement. I bet everyone was like,

Two-thirds of the members of Congress at some point had a mother standing in their office with a quilt panel. And then within a few years, the Ryan White Act provided $2 billion to sustain public health systems and hospitals across the country that were buckling from the weight of all of these dying people. And the fact that we could do it in a way that was also colorful and loving and warm and spoke to middle America made us a little bit of a Trojan horse.

But not everyone agreed with that approach. Angry funeral, not a sad one. The quilt makes our dying look beautiful, but it's not beautiful. It's ugly, and we have to fight for our lives. And, you know, one thing that ACT UP members were reacting to at the time was that a lot of the funerals of people who died of AIDS, they were being covered in, like, the arts section of a lot of major newspapers, right?

And as one person told me, it was sort of like the world was seeing their deaths as aesthetic events and not as political events. Like instead of their deaths being treated as news and politics, it was just a cultural event or something. And David in particular felt like that was what was happening with the quilt. I think the quilt itself does good stuff and is moving. Still, it's like making something beautiful out of the epidemic. Once I saw that

The people who organized the quilt and the quilt showings would allow anyone to read names, including President Bush. It was just so clear to me that we needed to demonstrate what the actual result of AIDS was. There was nothing beautiful about it. This is what I'm left with. I've got a box full of ashes and bone chips. You know, there's no beauty in that. I know I was adamant that

I didn't want this to be symbolic. The power in what we were doing was the utterly unvarnished truth. And I guess, you know, when I think about these two approaches, maybe it's sort of a false choice and you need both or whatever, but it feels like a dilemma. I'm

I know that I feel pulled towards the raw truth and expression of anger in the ashes action. Yeah. But I can also see the beauty of the quilt and the pragmatic political power it had. And I think that's a real question, especially for the people in pain. Like, where do you put your energy? Yeah. But what I found, and we'll get right into this after the break, is a couple of moments in this movement...

That just totally unraveled that question. All right. More in just a moment. This is Radiolab. I'm Lulu Miller. And we are back with our story about protests from Tracy Hunt. Okay, so I'm starting a whole new story now. Okay. And this is getting at like, if you're trying to push a government or the world to pay attention and make change, how do you do that? How do you do that while also being true to yourself?

your experience, your emotions, your ideals. Right. So I was looking back to the early AIDS movement for insights on some of those questions.

And a familiar name popped up. Hello. Good morning. Sorry. Good morning. A Dr. Anthony Fauci. I wasn't expecting you to pick up like immediately. The Fauci. The Fauci. The Fauci is in this story? Well, I'm here. If you want me to go away, I'll leave. No, no, do not. Please don't go away. The Fauci is actually a big part of the story. Well, I mean, yeah. Back in the 80s, early in the AIDS crisis, he had the exact same job that he has now. Like truly the same title? The exact same title, job.

job, everything. Wow. The head of NIAT. And back then he was studying immunology, the molecular architecture of fevers. Then he heard about this weird disease. HIV AIDS before we knew it was HIV. That in the United States at the time was afflicting mostly white, young, gay men. You know, who would have thought back in the 80s that you would have 78 million infections and 37 million deaths?

from a disease that no one wanted to pay attention to. His mentors at the time were like, what are you doing? You're on this path to success. Why do you want to work with AIDS patients? But I had a great deal of empathy for these gay young men. So?

He ignored his mentors. Now let's go to the lecture and join Dr. Anthony Fauci as he talks about AIDS. And he turned his career to focus almost completely on AIDS research. I'm working directly on AIDS, both clinically and from a basic science standpoint. It was a transforming time in my life. The amount of effort and energy that's being put into it by biomedical scientists.

As a scientist and as a physician taking care of these patients. And under his guidance, the NIH started to make huge leaps and bounds in AIDS research. Dr. Anthony Fauci is hopeful that the answer to this dreaded disease may be in sight. You know, you hear that story and you're like, wow, Fauci, great man. A great man then, great man now. So brave. Wow. Okay. AIDS activists at the time...

research, stupidity, incompetence. Did it f*** with Fauci like that? Dr. Anthony Fauci is deciding the research priority. Can I read you a little of Larry Kramer's open letter to you? Because it's so mean, so I feel like I have to ask permission first. No, no, no, of course. I mean, that was the famous San Francisco Examiner open letter to an incompetent idiot. Yeah, it's like, Anthony Fauci, you are a murderer. Your refusal to hear the screams of AIDS activists early in the crisis resulted in the deaths of thousands of queers.

With 270,000 dead from AIDS and millions more infected with HIV, you should not be honored at a dinner. You should be put before a firing squad. Right. That, I would say he was trying to gain my attention.

And he certainly accomplished his goal. He got my attention. Wow. Yeah. So that letter was published in 1988. Wait, but okay. So before we go on with Fauci, like, and so was he doing stuff like he made this move to go work on it, but then was he somehow doing something different?

Something wrong? Dangerous? Yeah. Well, there were a bunch of issues. This is Peter Staley. Long-term AIDS activist and LGBTQ rights activist. He was a big-time member of the ACT UP community. And he says that, sure, yes, yes. Dr. Fauci was doing a lot of work on AIDS, but... He was head of NIAID, and they were the primary institute at NIH that handled the bulk of AIDS research back then. So...

In essence, he was the head of AIDS research for the U.S. government. And we had problems with that effort. Back in the 80s, the drug trials that they were running. They had a pretty disgraceful track record of not enrolling the full diversity of patients. Tended to be really white and really male.

even though the numbers of infected women and African-Americans was increasing. And so like we're getting drugs that we don't even know if they work on anyone who's not a gay white man.

And the board was also making all these decisions without the input of people who actually were living with AIDS. You know, the board was just these doctors and researchers who were playing it. Kind of safe, frankly. You know, we had AZT. We had the first drug. But AZT was toxic. It had...

all these terrible side effects. And Peter Staley and others thought that there were lots of other drugs out there that could be even more useful. And we wanted a robust research effort on those drugs. But Fauci and his team... They just started testing the wazoo out of AZT. And the few times when they did have a new drug, it took years and years for it to make it to anybody with AIDS who could actually benefit from it.

And activists were like, people are dying now. He's not moving fast enough on the things we want. So they put together a list of demands and they decide to bring them to him at the NIH. Okay. In ACT UP land, that can't be as simple as showing up. On a beautiful, crisp morning. In Bethesda, Maryland. Onto the serene campus of the NIH. All these people. Over a thousand demonstrators from all around the country. Showed up.

and started marching. The cops were all ready, cops on horseback. They were quite prepared. There were also TV cameras and reporters.

And Peter knew that if we put on a really big, fancy display, that gives the media... A really colorful picture. You increased your odds of appearing on the front page. And he had these colored smoke bombs. Surplus military smoke grenades. Hidden behind protest signs. On the top of really long bamboo poles. So they marched along with others, but then at the right moment...

All at the same time... We dropped our poles, ripped off the signs, pulled the pins of these things, and then raised the poles back up. And these plumages of huge, thick red, orange, blue, purple... And pinks and greens... Started pouring out at the top of these poles. And beneath this massive rainbow war cloud, they charged... Through the crowd. And the crowd erupted...

And then it was just an entire day of well-orchestrated chaos. This is a major day of protest by AIDS activists in this country. I mean, everywhere you looked, something was happening. People were giving speeches. Black women talking about their experiences living with AIDS. They were people dressed up in lab coats.

making fun of scientists. There was singing, die-ins. One section of the lawn was transformed into a graveyard. Air horns punctured the noise of the crowd. Basically what we're doing is blasting the horns every 12 minutes to remind people that statistically right now, every 12 minutes someone in America is dying from AIDS. And at the center of all this noise and color stood four people dressed in hooded black robes.

And they carried a black coffin that had the words, F*** you Fauci, written on its side. They also had a really giant Fauci head impaled on a spike. And there was blood coming out of his ears, nose, and mouth, and his eyes. And then...

They burned him in effigy. They burned him in effigy? Yes. No more secret trials! ACT UP was publicly... Good trials for women! Taking that list of demands... NIH scientists need to work with activists! Shaking it in Fauci's face... You test mice while women die! And nailing it to his door. Whoa, that is intense. Yeah. And Fauci...

is sitting up in his office several floors up, looking out the window. They were really confronting me in a very, very aggressive way. And as he was taking it all in, I saw it from my window. Amidst all this chaos, the slight figure of Peter Staley get boosted up onto this ledge above the front door of the building. Yeah, I got on the overhand. You could see

that he was on this little overhang and started hanging up banners and the crowd cheered. But the cops were having none of it that day. And the police were going to climb up and get him. They launched a few of their own up onto the overhang and tackled me. The police are like scrambling. Lowered me down in the hands of a dozen cops. And they had to take him to the police van. And the police van is like in the back of the building. And because the building is now surrounded by activists, the only way to get him to the back of the building is to take him

through the building. So they handcuffed me behind my back and an officer grabbed my elbow and started hauling me through the first floor of building 31. And as we're going down this wide corridor, I see that familiar white lab coat on that short scientist coming towards me. He had handcuffs behind his back.

And this police officer was taking him away. And he passed me and he said, Tony? And he goes, Peter? And Tony said, are you all right? And I said, yeah, yeah, just doing my job. How about you?

He said, well, we're trying to keep operating under these conditions. And I said, well, good luck with that. We'll talk tomorrow. And I said, OK, Peter, see you later. And the cop looked at me like, what the hell is going on here? Wait, they know each other? Yeah. And this is the first little piece of the puzzle in explaining why this action was so different from the ashes action or even the quilt. And I'm going to get into that right after this break.

Radiolab will be back in a moment. Hi, I'm Lulu Miller. And I'm Tracy Hunt. This is Radiolab. And today we're talking about, well, kind of how you actually make change in the world.

And doing that by looking at a bunch of different kinds of protests that took place during the AIDS crisis. Right. And before the break, we heard from Dr. Anthony Fauci, who at the time was leading the country's efforts to find a cure for AIDS. And he was actually being targeted by ACT UP because they felt that he was failing the AIDS community with the type of research he was running. Right.

And when we left off, Peter Staley had just been arrested at a protest. And as he was being escorted away by police officers, they had this, you know, they ran into each other in the hallways of the NIH building.

And then it turns out that this whole time, Peter Staley and Dr. Fauci were actually friends. And, you know, that surprised the police officers at the time. And it also surprised us as we were reporting the story. Right. And so you were just getting ready to explain how they know each other, right? Yes. And why this particular protest was different from any of the other protests that had come before it. So we have to go back to 1988.

to that letter that Larry Kramer wrote to Fauci where he called him a murderer. Do you remember that? Yeah. The whole murderer thing? Of course, of course. When Dr. Fauci saw that letter, he thought... If somebody is that angry to be able to print that in a national newspaper, I mean, I got to find out what is it that has stimulated him to do that.

So he just called this guy who called him a murderer, called him on the phone and said, let's figure this out. And despite their differences. We know we came to an agreement that we both had the same common goal. Yeah. Well, I'm really surprised by that because like, you know, I'm thinking of like the storm, the NIH protests when people literally have like pictures of your heads on a, of your head on a stake and saying, you know, F you Fauci, uh,

Well, no one was really able to listen to their message because they were too put off by the tactics. And I think the thing that I was able to do was to separate the attacks on me as a symbolic representative of the federal government that they felt was ignoring their needs and

Dr. Fauci, I wonder if I can follow up on that. That's our host, Dad Amimrod. He was sitting in on the interview with Fauci. It's kind of an extraordinary emotional jujitsu that you're describing. I mean, people are saying horrible things, which could be read as symbolically about a person in a role or it could be taken quite personally. And you're saying everybody around you is taking it quite personally, but you somehow were able to

to shift posture. - Right, right. - Do you have any recollection of how you did it? Like what specifically got you out of defense and into receptive mode? - You know, I think it's a complicated thing. It really dates back to my family. My mother and father were very much people who were quite tolerant of different opinions. And part of not only my background, but the Jesuit training, both in high school and in college,

is that you care about people no matter who they are, and you keep an open mind to opinions. Once you become defensive and push back, you never hear what their message is. And once you listened to what their concern was, I got this feeling that, goodness, they're right.

Wow, it is so hard to picture a person in power responding like that today. You know, it seems like when someone spits on your face and says awful things about you, the main move you see is people screaming back louder or like blocking you on social media, not acknowledging or hating back. Yeah, I mean...

There's a part of me like when I hear this story where I'm just like, you know, that's like a really easy way to make himself look good. But at the same time, you know, even me who's like Miss Cynical can't deny the fact that that was like a pretty cool move on Stalci's part to turn that moment into a moment for like a conversation. Yeah.

And after that initial phone call, Larry Kramer actually connected Dr. Fauci with Peter Staley and a couple of other activists. Fauci swung his office door open. I said, it's time for me to put the theatrics aside and listen to what they're saying. And we had a very healthy back and forth. And you know, a little while after that, those phone calls turned into...

dinner parties. These famous dinners we would have with him in Washington. Sitting down around the dinner table of my deputy at the time, Jim Hill. They discuss ideas, strategy, medicine. How we can continue the dialogue of coming to some common ground. And now this is all still before Peter and others stormed the NIH. And this is actually where Peter would bring up the list of ACT UP demands, like...

Hey, Dr. Fauci, could you please pass the salt? And also, we think that you really need to diversify your trials. Hey, Dr. Fauci, this pie is so good. What'd you put in it? But you know what's not good? AZT. Let's start testing more drugs.

And Fauci... Well, you know, he kind of passed the buck. I mean, I had a lot of pushback from my own colleagues in the scientific community. He just had a lot of excuses. We were sick of hearing from him tell us for over a year... Dinner after dinner after dinner... I understand you. I agree with you. But I can't convince the executive committee. And we were like, screw that. Peter and the others were like, you know what? Empathy and listening and dinners...

It's not enough. So it was actually at one of these dinners

Peter told Dr. Fauci, So Tony, I got bad news for you. In a couple of months, we're going to descend on your campus with a massive demonstration to push these issues. And what did he say? He said, wait a minute. We're sitting here having dinner and sharing a glass of Pinot Grigio. You're going to storm the NIH? What are you talking about? He tried to talk us out of it. No, I did. You know, I said, Peter, are you sure that this is going to be a productive thing? He kept pleading that he needed a little more time and

And we said, well, you got a couple months. I said, oh, okay, fine. Thanks an awful lot. A couple months later, a thousand people show up to his door with his head on a spike. Yeah, well, what happened? What did happen? Was there tons of, did the media pick it up? There was a lot of media attention. And thanks to Peter's colored smoke bombs, it actually did make the front page of a couple of newspapers. But a lot of the media attention was not sympathetic.

Was just like, look at these... Was not sympathetic. Was not, look at these crazies who showed up at the NIH. Okay. But the thing that makes this protest different from the ashes action or even the quilt is that they were saying **** to somebody who was actually sympathetic to them. That demonstration...

was more about putting him between a rock and a hard place. We were the rock, and the hard place was the executive committee of the ACTG. This was about giving Fauci a very public boot in the ass. We wanted to make it politically difficult for them to ignore him and us. And so he got squeezed by ACT UP. And that squeeze was apparently exactly what he needed, because... He did...

kind of what we were hoping he'd do. He pushed the ACTG harder. And within a few months of that demonstration, the ACTG executive committee caved. They got pretty much everything they wanted. ♪

True. Like on that list, they got it all? Yeah. The ACTG decided to open up all of their committees. Activists and other people with AIDS were added to the panels. We got voting membership on the executive committee. They did diversify the people that they were testing. They did begin to start testing drugs that weren't AZT. And we started to reformat and refocus the clinical trials and the conducting of clinical trials towards HIV AIDS. They got what they needed.

Wow. Yeah. That is so not a story I feel like you ever hear. Yeah. But to be clear, the Storm the NIH action happened in 1990. It wasn't until 1996 that they actually had the drug cocktail that was giving people living with AIDS a much longer life. And so it was actually after the Storm the NIH action that

Larry Kramer was giving these angry speeches about how desperate the situation was. And David and Alexis throwing their loved ones ashes on the White House lawn. That happened after Storm D.N.A.H. And, you know...

You can certainly point to the Ashes action and other political funerals that ACT UP did during that time period as like, you know, not being as effective as Storm the NIH. But when the situation is so dire and things are so dark and people are so desperate, you

Maybe that moment called for a different kind of demonstration. That is exactly right. And this is me as a media scholar talking and a rather radical one. This is Alexandra Juhasz. She is a professor of film at Brooklyn College, and she worked in ACT UP. I don't know that you're a media maker. Mm-hmm.

One goal is to, quote unquote, change someone's mind. Yeah. Okay. That's a real goal. And you make certain kind of work to, quote unquote, change somebody's mind. There was an organization at this time that I knew called AIDS Films. And they made a number of short narrative, highly polished films. And those were definitely change mind kind of films because they were feel good. They looked familiar. Right.

Now, that's a reasonable goal, but we're not sure that stop the church or the ashes action or political funerals, the goal is to change someone's mind. The goal is to express your anger. The goal is to express your desperation. The goal is to say no. The goal is to say this is wrong. Those actions by ACT UP were to express defiance.

and to put defiance on the map. You know, she was like, protest is about making sure that this thing is never going to go away. And I kind of had a moment like that because I was talking on the phone with a friend, and all of a sudden I heard outside my window, say his name, George Floyd. And part of me was like, again? Really? Did you really think that?

For a second, yes. I should say that where I live, like, there were protests almost every day during the summer. And so I had actually gone a few months without hearing any. And then it was happening outside my window. And I did have that reaction. And then I was like, wait, what am I annoyed with? What am I really annoyed with? And I realized, like, what I'm really annoyed with is the fact that another Black man was killed in Philadelphia.

And that's why the protest was happening again. And I also realized that, you know, it was a reminder, you know, we're not done.

And David and Alexis and all the other people involved in ACT UP, every week it was like another action and it was another funeral and then there was like another action. It kept going and going and going and there hadn't been really any moment to like just stop and assess all the trauma they've gone through. Yeah!

But after they made it through the mountain police to the fence and let go of those ashes. This incredible release of energy out into the universe. They say there was this moment. The magnitude of what had just happened hit me. I just began to sob convulsively. One of ACT UP's slogans had been, you know, turn your grief into rage.

Larry Kramer was very fond of saying that. But to really experience our grief. Oh, wow. Like if Warren, I 100% knew then and know now, he would have approved and, you know, been proud. This was my friend, Kevin Michael Kick. He was 28 years old and he died on Halloween 1991.

The main reason I'm here is to scatter my own ashes. I'm going to die of AIDS in probably two years, and that is why I'm here. I'm here on behalf of my father, Alan Danzig, who died when he was 57 years old. I really needed this. My name is Eric Sawyer, and I scattered the ashes of Larry Kurt.

Larry Kurt was 60 years old. He was the original Tony in West Side Story on Broadway in 1957. Larry was to have his last professional performance at the White House. He was invited to a party to sing with Carol Lawrence. They were going to sing Somewhere There's a Place for Us. And he planned to come out as a person with AIDS.

And when the White House administration found out he was going to do that, they conveniently lost his music just before he was to go on. I came to scatter the ashes of my lover, Michael Tad Hippler. Truth to tell, I had scattered all of his ashes that I had, but I was sitting at breakfast with his sister, and I told her about this demonstration, and her eyes lit up, and she said, "Hey, do you want some ashes?"

So I love you, Mike, and I know you would have wanted to be where you now are. You're welcome, Lulu. But before we go, can I just like tell you about one more protest? OK, OK. So ACT UP, you know, they used to do this thing where they would identify people that they felt were responsible or had power to actually change things.

And if those people, you know, weren't going to like listen to them or, you know, have a dinner with them like Dr. Fauci did, ACT UP would identify those people and then... And then target those individuals. For an example of that, he told me the story about the time that...

Jesse Helms. Do you remember Jesse Helms? The homosexual lesbian crowd. Oh, yeah. Well, they don't like me and I don't like them. Senator Jesse Helms, enemy number one. His hardline conservative views earned him election to the Senate five times. He passed this rule that said that if you had AIDS, you couldn't come to the United States for a really long time. And he successfully passed that? Yes. Wow.

Wow. It was a rule until the Obama administration. Man, okay. He also was behind banning immigration from Haiti because a lot of people from Haiti had AIDS. He also tied the hands of the CDC, saying that they basically couldn't provide grants for HIV prevention that mentioned gay men. Those...

of us who feel that there's a spiritual and moral aspect to this. It was hitting us harder than any. And the CDC couldn't target prevention messages to us at the height of the epidemic. It was just evil, evil, evil stuff. And so...

ACT UP decided to mess with him. I had had enough and decided to make it personal and take it right to his house. And we put a gigantic condom on him. They put a condom on his house.

Wait, over the house? Like over it? Like stretched over the house? Just stretched over the house. Wait, how do you put the jacket? YouTube it and you'll see. It's on YouTube? Wait, I'm going to look this up right now. I encourage you after this to just Google like ACT UP. Jesse Helms condom. I don't know if I have the restraint to wait.

Act up, unfurled. Oh my goodness. I can see you guys. You're on to Ruth. Yes. Oh my goodness. So we've got a big, mauve-ish giant condom, like with a tip. It has a tip and everything.

A reservoir tip. Yes, yes. As we all learned in Sex Ed, you have to like pull the tip a little and then roll it down. Yes. Okay. A condom to stop unsafe politics. Helms is deadlier than a virus. Police were called to the scene, but they didn't arrest anyone. You mess with us and you're going to wake up one morning with a condom on your house. Yeah.

And I was like, OK, what does that do? You know, and Peter Stanley was like, You get the larger public to laugh at the politicians. The chair recognizes Senator Helms. It diminishes their power. A bunch of them climbed up on my house in Arlington and hoisted about a 35-foot canvas condom one day in protest of me. He railed against us on the floor of the Senate. They march in the streets and they defy you.

to say anything about them. I wish they'd shut their mouths, go to work, and keep their private matters to themselves and get their mentality out of their crotches. A leading Democrat stood up and said, Oh, you know... Sir, when we started this colloquy, I thought I was on your side, particularly on the First Amendment. These activists have a right to have their own First Amendment rights. And under the First Amendment, people don't have to shut their mouths. They have a right to speak. Well, they could speak just so long as...

They don't offend anybody else, I suppose. Well, that's not the test. He got immediate pushback. And after that? He never got another anti-AIDS Helms Amendment approved by the Senate after that action. Reporter Tracy Hunt. This episode was produced by Tobin Lowe and Annie McKeown.

Special thanks to Elsa Hone-Sun, Joy Episala, Deborah Levine, Theodore Kerr, Ben McLaughlin, Catherine Gund at Diva TV for the use of the NIH protest footage, Diane Kelly for fact-checking, and Catherine Fall for additional archival research. Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler.

Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Suzy Lechtenberg is our executive producer. Dylan Keith is our director of sound design. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Rachel Cusick, Akedi Foster-Kees, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gable, Maria Paz Gutierrez, Sindhu Nyanasanbandhan, Matt Kiyoti, Annie McEwen, Alex Neeson, Sarah Khari, Anurazkot Paz,

Sarah Sandbach, Ariane Watt, Pat Walters, and Molly Webster, with help from Andrew Vinales. Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger, and Natalie Middleton. Hi, my name is Michael Smith. I'm calling from Pennington, New Jersey. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, the Simons Foundation Initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation.

Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

There's a lot going on right now. Mounting economic inequality, threats to democracy, environmental disaster, the sour stench of chaos in the air. I'm Brooke Gladstone, host of WNYC's On the Media. Want to understand the reasons and the meanings of the narratives that led us here, and maybe how to head them off at the pass? That's On the Media's specialty. Take a listen wherever you get your podcasts.