Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

Ryan Reynolds here for, I guess, my 100th Mint commercial. No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. I mean, honestly, when I started this, I thought I'd only have to do like four of these. I mean, it's unlimited premium wireless for $15 a month. How are there still people paying two or three times that much? I'm sorry, I shouldn't be victim blaming here. Give it a try at mintmobile.com slash save whenever you're ready. For

$45 upfront payment equivalent to $15 per month. New customers on first three-month plan only. Taxes and fees extra. Speeds lower above 40 gigabytes. See details. Hi, it's Phoebe. We're heading back out on tour this fall, bringing our 10th anniversary show to even more cities. Austin, Tucson, Boulder, Portland, Oregon, Detroit, Madison, Northampton, and Atlanta, we're coming your way. Come and hear seven brand new stories told live on stage by me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr.

A shirtwaist, or a waist as it also would have been known in the early 20th century, was a crisp cotton blouse.

was a very fashionable item of clothing. It would have been worn probably with a skirt, so tucked in. And of course, you know, the smaller the waist, the better. And it might have been embellished with lace or colored stitching on the front. Shirtwaists were made popular by the Gibson Girl, a character created in the 1890s to represent what was called the New American Woman. ♪

The Gibson girl was fashionable, well-educated, and rich. She knew all the latest trends, and she played sports, like tennis or golf, and rode bicycles. In illustrations, she was always tall and very well put together, wearing a shirtwaist. In the early 1900s, thousands of shirtwaists were made every day in New York City. Tell me a little bit about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Where was it? What did it look like?

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, or the Triangle Waist Company as it was known at the time, was located in the top three floors, so the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of a building that was known as the Ash Building. That building was at the corner of Washington Place and Green Street, just east of Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village, New York.

Marianne Traciotti is the director of Hofstra University's Labor Studies program. It was considered a state-of-the-art, beautiful neo-Renaissance building when it was built in the early, around 1901, 1902.

And I'm sure that most people who walked past that building, unless they knew people who worked in there, were likely unaware that the factory even existed in the building as they went about their daily lives. Most of the people working inside the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were women. This was an industry that was considered appropriate for women to work in because, you know, there were other women there. It was a very...

female-centered place in a lot of ways. Some of these women, they enjoyed the work. They had fun. They made friends. And so parents would feel like this was a safe place for their daughter because they knew some of the other women who were there or maybe some of their other female children were there. So once someone established a foothold in an industry, it was typically the case that they brought their friends and relatives with them.

Many of the women who worked inside garment factories were recent Italian and Jewish immigrants. Some men worked in the factories, too, but they got higher paid positions, ones that were thought of as more skilled, like cutting fabric for the women to sew. What were the rules about the age limit for those working in the factory?

Well, this was the early 20th century before exploitative child labor was outlawed in the U.S. And so, sadly, child labor was a real thing. Children would sometimes lie about their ages in order to get jobs. We know that the youngest workers at Triangle, we know for sure that they were as young as 14. There were no rules about how long the workday could be.

And the girls and women would often work in the factory for 11 or 12 hours straight. And the weeks were long. Workers worked six days a week. And if they had objections to that, they were told, well, if you don't come on Saturday, don't come back on Monday. The factories...

were loud, right? The machinery was very loud. The workspaces were crammed to capacity with machines and people. In some industries, we have stories of girls who had longer hair and their hair would get caught in machinery and they would be scalped or their fingers would be, you know, pieces of their fingers would be cut off.

In 1904, an 18-year-old named Clara Lemlich and her family moved to the United States from Ukraine to escape anti-Semitic violence. Two weeks after she got to New York City, she started working in the garment industry. She was horrified by factory conditions. As she put it, the women and girls working in them were seen as, quote, "...part of the machines they were running." Clara started campaigning for changes, but she didn't get any.

She wrote op-eds for local papers. She joined the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union. In November 1909, thousands of garment workers gathered at a hall in downtown New York.

Clara Lemlich attempted to speak a few times and was never permitted to speak. She was a small woman. Could she possibly contribute to the conversation? And eventually, a number of people started shouting, "Let her speak! Let her speak! Let her speak!" And Lemlich went up to the podium and said, "I've got something to say!" And then she proceeded to berate the men in the audience for standing around and engaging in speculation and conversation.

when there were serious problems. She called for a strike. And the people in the audience were mesmerized and motivated and inspired by what she said, and the women heeded the call. They stopped working. It was called the uprising of the 20,000. The striking women sacrificed their pay. They risked getting put on industry blacklists and never hired at any of the factories again.

And they risked their reputations. It was considered unladylike in 1909 to be unruly.

Women unchaperoned in the streets demanding, you know, that they be treated better and that their wages be raised. And this was considered unseemly behavior. They also risked, you know, being abused physically, being taunted verbally. The women who participated in the uprising of the 20,000, they were called prostitutes.

They were, you know, taunted and jeered. They were assaulted by police. Lemlich had several of her ribs broken. The strike caught the attention of upper-class women in New York, including Ann Morgan, J.P. Morgan's daughter, and Arabella Huntington, one of the richest women in America. They worked with Clara Lemlich and other union leaders to fund the strike. They paid for people's food and rent. They bailed women out of jail.

And they even joined the picket lines. And so they came downtown to support them. And they were known as the mink brigade because they stood with the working class women and they were distinguishable because of the finer clothing that they wore. And they did this to protect the women from being brutalized by police. The strike lasted for more than two months.

By the end, hundreds of factories agreed to the workers' demands for higher wages and shorter work weeks. But the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory didn't agree to anything. The strike was largely a victory for the women working in the garment industry, except for the women workers at Triangle. And that had fatal consequences for them. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal. ♪

So the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was owned by two immigrants, Max Blank and Isaac Harris. They were themselves garment workers. And they moved up the ladder and eventually became business partners and owners. And their name, by which they were known, their nickname, was the Shirtwaist Kings. Because they were quite successful in the industry. But they also cut corners.

Between 1902 and 1910, there were four fires in their factories. Each fire happened in the morning, when no one was in the building, just extra inventory, which Blank and Harris could collect insurance money on in the case of an accident. They were also notoriously anti-union.

They refused to give up control. They refused to allow union organizers to come into the shop. And that's, I mean, that's a reason why a lot of employers will hold out during a strike. They might even be okay with paying better wages. They just don't want to lose control. A little over a year after the strike ended, on March 25th, 1911,

Around 600 people, mostly young women and girls, showed up to work at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. It was a Saturday, an early spring Saturday, and a number of the workers were Jewish, and this would have been their Sabbath, and they were not permitted to observe the Sabbath. Working on Saturday was required.

I imagine as 5 o'clock loomed, the girls were getting really excited because it was a Saturday night and some things don't change. I mean, you know, young women, particularly women who maybe they have, you know, boyfriends or an outing with girlfriends planned, and they're really excited. And we know that they were singing in the building that afternoon as 5 o'clock was rolling towards them.

It's thought that around 4.45, someone was having a cigarette on the eighth floor, and some of its ash landed in a trash can at a fabric cutter's desk. Smoking wasn't allowed in the building. We don't know if he dropped the cigarette butt into the bin or flicked an ash, but what we do believe is that the ash in the bin ignited the scraps of fabric in that bin. They erupted into flame, and...

And there were so many fibers in the air that the air transported the fire, and the floor had not been swept. And so there were many scraps of fabric on the floor, so that also helped too.

And before long, the eighth floor was ablaze. And fire burns up, not down. So workers on the seventh floor and below really weren't in much danger. But workers on the ninth and tenth floor were.

Were there ways for workers to communicate from floor to floor? So there was a telephone system, and the way it worked was the switchboard operator was on the 10th floor, so if you had to call, say, the 9th floor, you would call up to the switchboard operator on the 10th floor, and then they would take it from there and connect you or make a call if you had to reach someone. If the owners or any of the factory managers were in the building...

they would have been on the 10th floor. So we know that a worker on the 8th floor did contact the 10th floor, but the switchboard operator never made a call to the 9th floor. And I have to tell you, I can't blame her. If I got a phone call that there was a fire in my workplace, in an era in which fire drills did not happen—

in which I knew that there were minimal, there were no fire extinguishers. I mean, there was nothing there to put out the fire. I'm not so sure I would keep my head and be able to call other people. And certainly she did not. She did not make the call to the ninth floor. So only the workers on the eighth and tenth floors knew the building was on fire. From the tenth floor, people were able to climb to the roofs.

There, NYU students helped them get on to neighboring roofs. On the eighth floor, people rushed to the stairwell and an elevator. The elevator that held 15 passengers was crammed with as many as 30. If the elevator was filled, there are stories of girls who leapt on top of the heads of the other workers who were in the elevator, and some of them actually jumped into the elevator shaft. But

But there is a hero in this story. His name is Joe Zito. Joe Zito was a 19-year-old Italian immigrant elevator operator in the building. And when he realized what was happening, he took workers down to safety and they left. And he could have gotten out of the elevator and walked away from the building and looked on in horror along with everybody else and think, you know, there but for the grace of God go I. But he didn't.

He stayed in the elevator and he kept taking it up and bringing it down and taking it up and bringing it down until the elevator ceased functioning because, you know, the stress from the heat and the fire. The women and men who were working on the ninth floor didn't know anything about the fire until they could see it. To try to get out, they ran to the doors, but they were locked.

And the theory is that these doors were locked for two reasons. One, to keep out union organizers. And two, so that workers couldn't sneak out having stolen items from the factory. We also know that theft was almost non-existent. So almost certainly they were locked primarily to keep out union organizers. Fire trucks arrived and tried to get ladders to the people trapped on the ninth floor.

But ladders on fire trucks in New York City in 1911 only went up to the sixth floor. There was no law in a city of skyscrapers, there was no law mandating that fire ladders go higher than that. So they could not reach the girls. So people on the ninth floor went to the fire escape. But it was not regularly tested. And when workers tried to escape,

On the fire escape, it collapsed and they died. In fact, we do know that at least one worker was impaled when the fire escape collapsed. Since it was a Saturday evening in the center of the city, plenty of people were around. And soon, a crowd formed around the building. The people on the street noticed women standing in the windows of the ninth floor as if they were getting ready to jump.

And when the first workers went out onto the ledge to jump, people begged them, don't do it. And the fire department had nets with them that they held out, hoping that maybe that would be a way to catch them before they hit the ground because the odds were not good that they would survive a jump from the ninth floor onto the pavement below. And they crashed right through those nets.

So the nets were useless. And people just stood there in horror as workers looked out the window, tiptoed onto the ledge, took their chances and jumped. Around 60 people died jumping from the ninth floor. A firefighter later said, sometimes the women came down with their arms locked about each other. We have these really poignant eyewitness accounts of

of watching them look out the window and then come out onto the ledge, maybe holding hands with someone else, and then just jumping. There was a young woman

AP reporter named William Gunn-Shepard, who happened to be in the neighborhood when the fire broke. And he rushed to the scene and reported what he saw. And he describes what he heard. And he says it was the most terrible sound he had ever heard. He would never forget it as long as he lived. Thud. Dead. Thud. Dead. Thud. Dead. After 15 minutes, the fire had burned through the top floors of the factory.

So in total, 146 workers died that day. 129 of them were women. The youngest was 14, the oldest was 43, and 17 of them were men or boys. In the days after the fire, there were so many funeral processions that they'd sometimes run into each other.

There are stories of people starting in one procession and then there's an intersection and one procession sort of bleeds into another and then they split up and then, you know, the funeral marcher realizes they're not even in the right procession anymore because there's so many going on. I mean, day after day, funeral procession after funeral procession. And you can imagine that some people, you know, residents of the Lower East Side, for example, probably attended multiple ones of these. There were...

Seven, I believe seven pairs of sisters who worked in the factory. So some pairs of sisters were broken up because one died, one survived, and others, both of them died. The Maltese family, the mother and her two daughters died in the fire. So the Maltese family lost all of its women in one afternoon.

So families were just crushed by this. And their grief eventually turned into determination, determination to make Blank and Harris pay, and determination to ensure that horrible, preventable tragedies like this one did not happen ever again. We'll be right back.

Support for Criminal comes from Ritual. I love a morning ritual. We've spent a lot of time at Criminal talking about how everyone starts their days. The Sunday routine column in the New York Times is one of my favorite things on earth. If you're looking to add a multivitamin to your own routine, Ritual's Essential for Women multivitamin won't upset your stomach, so you can take it with or without food. And it doesn't smell or taste like a vitamin. It smells like mint.

I've been taking it every day, and it's a lot more pleasant than other vitamins I've tried over the years. Plus, you get nine key nutrients to support your brain, bones, and red blood cells. It's made with high-quality, traceable ingredients. Ritual's Essential for Women 18 Plus is a multivitamin you can actually trust. Get 25% off your first month at ritual.com slash criminal.

Start Ritual or add Essential for Women 18 Plus to your subscription today. That's ritual.com slash criminal for 25% off.

The Walt Disney Company is a sprawling business. It's got movie studios, theme parks, cable networks, a streaming service. It's a lot. So it can be hard to find just the right person to lead it all. When you have a leader with the singularly creative mind and leadership that Walt Disney had, it like goes away and disappears. I mean, you can expect what will happen. The problem is Disney CEOs have trouble letting go.

After 15 years, Bob Iger finally handed off the reins in 2020. His retirement did not last long. He now has a big black mark on his legacy because after pushing back his retirement over and over again, when he finally did choose a successor, it didn't go well for anybody involved.

And of course, now there's a sort of a bake-off going on. Everybody watching, who could it be? I don't think there's anyone where it's like the obvious no-brainer. That's not the case. I'm Joe Adalian. Vulture and the Vox Media Podcast Network present Land of the Giants, The Disney Dilemma. Follow wherever you listen to hear new episodes every Wednesday. After the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire, the owners of the factory, Max Blank and Isaac Harris,

invited reporters from the New York Times to Harris' house. They defended themselves and said they'd done all they could to make the building safe. But New Yorkers were angry. A week after the fire, thousands gathered at a rally at the Metropolitan Opera House. A union leader named Rose Schneiderman gave a speech to the crowd. She said, quote, "...the life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred."

Less than a month after the fire, the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were indicted with manslaughter in the first and second degree. The conviction, were they to be convicted, Blanken-Harris hinged on whether or not they knew for a fact that the doors had been locked. Blanken-Harris hired an attorney named Max Stoyer, one of the most sought-after lawyers in the city. The judge presiding over the case was Thomas C.T. Crane.

Years before, he'd been the Tenement House Commissioner and was blamed for an apartment fire that killed 20 people. Around 100 witnesses testified at the Triangle trial. Most were workers who'd survived the fire. Others were the firefighters and police who'd responded. And Stoyer's strategy was to undermine the credibility of the witnesses. He persuaded the judge not to allow emotional testimony about the fire.

Witnesses couldn't describe what it felt like to watch women jumping from the ninth floor. Many of the workers who testified at the trial didn't speak English well, so they spoke in Yiddish or Italian. Not everyone in the courtroom could understand them. The jury deliberated for less than two hours. The jury was not convinced that Blank and Harris were responsible, and so they acquitted them. The jury said that the prosecution...

did not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Blank and Harris knew the doors on the ninth floor were locked. After the trial, Blank and Harris were sued more than 20 times by family members of the victims. In the end, Blank and Harris paid $75 to families for each worker who had died in the fire. And they also had really great insurance. Their insurance payout was more than they needed to cover the damages from the fire.

$60,000 more. And so they made more money from the insurance payout than they ended up paying to the families of the victims. So this was, it was not a loss for them. They opened a new factory. Shortly after, Max Blank was ordered to pay a fine for locking the new factory's exit doors, $20. But Blank and Harris never recovered their reputations.

By 1918, they closed their doors. Did New York City change its workplace rules after the fire? It's hard...

To overstate the extent to which the Triangle Fire changed New York City and New York State and the U.S., actually. New York State changed its rules after the fire. There was a fire safety division that was established and put under the purview of the Fire Department of New York, FDNY. The American Society for Safety Professionals, which is the oldest and the largest organization of fire.

Safety professionals in the country was established almost immediately after the fire. In fact, their motto is born out of the ashes of the Triangle Fire. And two years after the fire in 1913, New York City held citywide fire drills. All five boroughs, schools and other places were instructed in how to respond when a fire breaks out.

New York also created a Committee on Safety to visit workplaces around the state and think about ways to make them safer. Its executive director was a woman named Frances Perkins. Frances Perkins was born in Massachusetts in 1880. Her father taught her Greek grammar when she was eight years old. And even though it wasn't typical for women to go to college, she did. Frances Perkins majored in physics at Mount Holyoke. Her classmates called her Perk.

and she was elected class president. In her final semester, she took a class on American economic history. One of its requirements was to visit working mills around the Connecticut River. She was shocked by their conditions. She became a social worker and eventually moved to New York City to get her master's in political science from Columbia. On the day of the fire, Frances Perkins was having tea with friends next to Washington Square Park.

They heard the fire trucks and decided to go see what was going on. She said, The people had just begun to jump when we got there. Quote, I can't begin to tell you how disturbed the people were everywhere. It was as though we had all done something wrong. We were sorry and felt as though we had been part of it all. After the fire, she traveled around New York State to visit factories and spent years working to improve their conditions. She said,

I was a young person then, but I was the chief. I was the investigator. And this was an extraordinary opportunity to get into factories, to make a report, and be sure it was going to be heard. And they reported their findings to the New York State Legislature. And 20 laws, I believe we can trace 20 laws back to the recommendations of the Factory Investigating Commission.

Frances Perkins' work helped pass the most thorough set of laws protecting workers in the country. Soon, other states began to model their own laws on New York's. She then became New York's industrial commissioner. She was appointed by the governor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In 1932, when Roosevelt was elected president, he asked her to join his cabinet as the secretary of labor. She told him she'd take the job only if he agreed with her policy priorities.

She wanted federal support for a 40-hour work week, minimum wage, unemployment payments, and Social Security. Roosevelt agreed, and Frances Perkins became the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet. I mean, Perkins really was the driving force behind much of the legislation that we know as the New Deal. She worked to pass the Social Security and Fair Labor Standards Acts, and later said...

The New Deal was born on March 25, 1911, the day of the Triangle Factory fire. So my mother was a garment worker. My mother and my grandmother and most of my aunts were garment workers and members of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. And I learned about the Triangle Fire when I was in middle school. And my mother told me years ago that we knew we were safe in my factory because of what had happened to those poor girls at Triangle.

The Ash Building, the building where the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire happened, is still standing. But for more than 100 years, it was unmarked, except for a small plaque. It would be easy to walk by without seeing it. Marianne Traciotti is the president of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. She helped organize a centennial remembrance in 2011.

And, you know, one of the people who came to New York was Kalpona Akter, the Bangladeshi garment worker organizer. And, you know, she was really moved by what she saw because she felt a real kindred spirit with Clara Lemlich. You know, and as she said in...

Bangladesh, it's still 1911, because these kinds of things are still happening. So, you know, it was then that we really realized, yeah, this is great that we're doing this on March 25th this year and every year, but there should be something on that building every day that says to people who walk by, hey, you know what? Something really important happened here, and you should know about it. We'll be right back.

Good morning. I'm Martin Abramowitz. I met Martin Abramowitz at his house in Newton Center, Massachusetts. Growing up, were you close with your father? My father died when I was very young. My father died in 1947. I was not yet seven years old. Martin's father was 54 when he died from heart disease. You don't have to be...

married to a psychotherapist or to have had many shrinks of your own to know that the loss of a parent early and the aftermath can be really very powerful. In my own case, the power was compounded by the fact that in those days, often kids were not told that their parents had died. And I was told a story that my father had

was ill and had moved to Florida from New York for recuperation. And I went through about two years supposedly believing that, but not knowing exactly what kind of sadness was percolating within me.

So you just thought he was getting better. You had no idea that he had died. Yeah, I don't know if I was conscious enough, smart enough to think he was getting better. I just, I think a part of me knew he was gone, but nobody articulated it. Martin Abramowitz's father, Isidore, moved from Romania to New York City in 1902. And when he was a teenager, he started working in the garment district.

When did you first learn that he had worked at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory? Okay, so it was not until my early 20s, early 1960s, I was working for the New York City Welfare Department, and we were going out on strike. And I mentioned that to my mother, and she said, you know, Daddy,

was a union member and was involved working for the Triangle Company at that time. But he was lucky, said my mother, because he was out making a delivery at that time. So she said that luckily he, did you ask any more questions? That was it. That was it. And so for years, I was very happily walking around saying my father had a labor history and luckily escaped the fire and that was it.

That's all Martin knew for decades. Then, in 2003, he came across a book that had just been released called Triangle, The Fire That Changed America. And I was wandering through a bookstore on my lunch hour at work and just went to the index. And there is Abramowitz Isidore, and he has this central role. What Martin Abramowitz read changed.

was that the fire had started in his father's trash bin. What did you think when you saw that? Well, I was amazed. So my first question to myself was, was this my father? His father was 18 when the fire happened. The book identified Isidore Abramowitz as a fabric cutter, but it would have been unusual for someone so young to hold that position. So maybe there's another Isidore Abramowitz floating around.

Well, there's no way to check personnel records. They were destroyed in the fire. So I went to the—this is 1911, remember? So I went to the 1910 census. And if I could just show you this. So this is the 1910 census. This is the 1910 census.

And this is on Orchard Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. This is the Bromwoods family living together with a few boarders as well. It's another way they made some money and supported themselves. And going way over to where we talk about occupation, and he lists himself as a cutter in ladies' waists. The author of the book where Martin found his father's name, David Vondrelli,

had learned about Isidore Abramowitz by looking at records from the trial of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory owners. The transcript of that trial was housed in a Manhattan office building that later burned. So the transcript of the trial was destroyed by fire as well as the company itself. Vandrelli, who's an investigative reporter for the Washington Post,

found a transcript of the trial in a kind of obscure little library in Brooklyn. The transcript revealed that Martin's father testified about the moment the fire started at his workstation. So my father described the layout of the tables and where he was and was asked, what did you do when you first saw the flames? And Martin

There's a very pregnant pause in the transcript. He doesn't answer the question. There are no details about Isidore's reaction in the transcript, only the words, no answer. And I think he must have paused. It must have been an emotional pause. He must have just needed time to compose himself. And they passed over that question and came back to it later.

What he did was grab for whatever was around. I'm not remembering now whether it was water or sand, a bucket, and try to put it out. But it didn't work? It did not work. What did you think when you read that? I just felt so bad for my father. You know, under any scenario, whether he just happened to be an innocent bystander or whether it was his

Cigar ash that started it all. He had to have carried with him an enormous amount of guilt. And I'd been haunted for years. I was haunted by the possibility that he carried this with him all his life. Eventually, Martin's father, Isidore, opened his own clothing factory. But after the Great Depression, he had to go back to the same job he'd had at the time of the fire, being a cutter for someone else.

In 2016, Martin Abramowitz heard that New York had approved funding for a permanent memorial to the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. He looked up the people in charge of the project, and he called Marianne Traciotti. The two talked for a while. They talked about the fire and the plans for the memorial. Martin told Marianne about his father. She told him about her mother and grandmother.

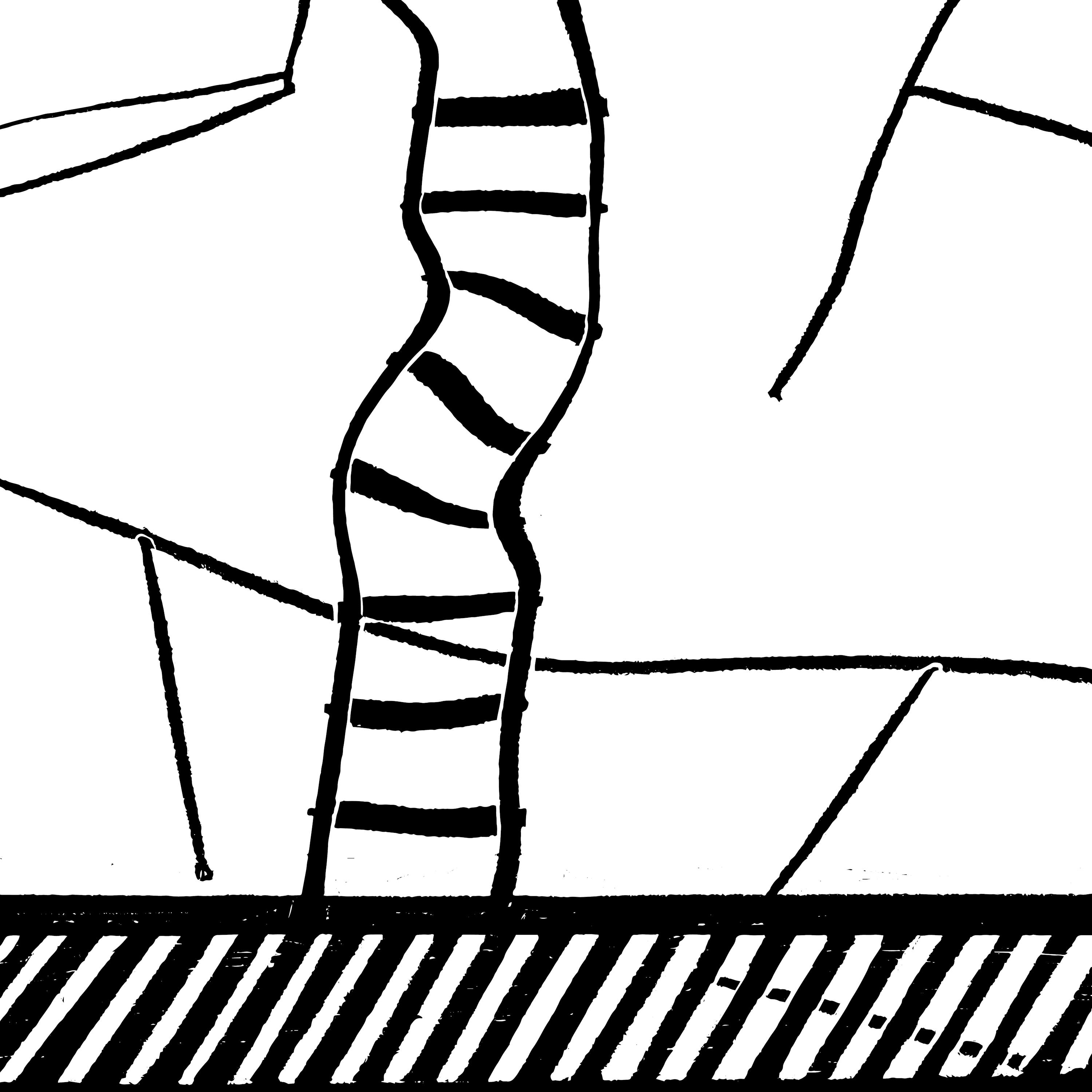

After their call, Marianne invited Martin to join the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. A few years earlier, they'd put out a call for designs for the memorial. There were more than 100 submissions. The winning design was called Reframing the Sky. By a two-person team, Richard Junieu and Uri Wegman from Queens. ♪

And their design basically is a ribbon made out of steel. It begins at the ninth floor of the building and it cascades down the corner of the building, kind of twists as it goes down the side of the building the way a ribbon would. And then at about 12 feet above the ground, it splits. And so it goes from vertical to horizontal.

And one side goes along Washington Place on the building, and the other side goes along Green Street. And in those horizontal parts of the ribbon, the names of the workers have been stenciled. So that light passes through them. The memorial was dedicated on October 11, 2023. Martin Abramowitz was there for the dedication. I...

had a chance to go up to the eighth floor of the building. The floor's been entirely remodeled. It dropped ceilings and was circled with glass windows and conference rooms, blah, blah, blah. And I went to one of the conference rooms where, in fact, you could look out and see the ground, of course, nine floors below. And...

I sobbed uncontrollably. I could see those girls standing there on that precipice, and I could feel the hope or the illusion that maybe they could make it if they jumped. It was just, okay, I'll break a leg, but I won't die. In some ways, the memorial... There is no compensation for the death of these 146 people, but in some ways, the memorial...

begins to do them justice. And if a descendant of Isidore Abramowitz is able to participate in doing justice to the memory of these workers, you know, that's important to me. Criminal is created by Lorne Spohr and me. Nydia Wilson is our senior producer. Katie Bishop is our supervising producer. Our producers are Susanna Robertson, Jackie Sajico, Lily Clark, Lena Sillison, and Megan Kinane. Our engineer is Veronica Simonetti.

Julian Alexander makes original illustrations for each episode of Criminal. You can see them at thisiscriminal.com and sign up for our newsletter at thisiscriminal.com slash newsletter. We hope you'll join our new membership program, Criminal Plus. Once you sign up, you can listen to Criminal episodes without any ads, and you'll get bonus episodes with me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr, too. To learn more, go to thisiscriminal.com slash plus.

We're on Facebook and Twitter at Criminal Show and Instagram at criminal underscore podcast. We're also on YouTube at youtube.com slash criminal podcast. Criminal is part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. Discover more great shows at podcast.voxmedia.com. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal.